The Last Waltz

By David Skolnick

The Last Waltz (United Artists, 1978) – Director: Martin Scorsese. Stars: The Band (Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel and Robbie Robertson), Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Van Morrison, the Staple Singers, Dr. John, Neil Diamond, Muddy Waters, Joni Mitchell, Ronnie Hawkins, Emmylou Harris, & Eric Clapton. Color, Rated PG, 117 minutes.

While I’m a big fan of both The Band and this film, I knew next to nothing about the group when I first saw The Last Waltz. My father, who loves The Band and had already seen the movie, woke me up one night around 10 p.m. – I was 10 years old at the time – and said the film was being shown nearby at midnight. Would I like to see it? Of course, who wouldn't want to sneak out of the house late at night with their dad to watch a concert movie?

To say I was completely blown away would be an understatement. The first thing shown on the screen at the start is: “THIS FILM SHOULD BE PLAYED LOUD!” The film projector guy was just following orders.

My love of The Band began that night. To see them play several of their great songs, and bring out many of my favorite musicians including Neil Young, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton and Bob Dylan, to perform with them, was an incredible experience. (Shortly after seeing the movie, I got my hands on The Best of the Band on cassette, and “borrowed” – and never returned – the triple-album soundtrack of the movie from my stepmother.)

I've seen The Last Waltz about 30 to 40 times over the years, as it was practically played to death for a few years on VH1 and during PBS pledge drives. It was on Netflix until a few months ago, and before it left I took yet another trip down Memory Lane and saw it once again.

As with other rock documentaries, The Last Waltz, has a nasty habit of clashing reality with fantasy. However, it is entertainment and not facts that is important when making a movie. Distorting the truth at times doesn't stop The Last Waltz from being one of the greatest rock films of all-time.

The film, directed by Martin Scorsese, showcases The Band's final concert with the five original members on Nov. 25, 1976. Scorsese's inexperience directing a rock-and-roll concert is apparent right away as the film opens with the group singing “Don't Do It,” one of their two Top 40 songs. The Band closed the four-plus-hour concert with that song.

We then get our first interview with a member of The Band. It's Robbie Robertson, and he talks about the group's final concert being at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, the first facility in which they performed as The Band. Robertson talks of the last concert in philosophical terms and if there was any doubt that he was the star of the movie, the opening interview eliminates it.

It's back to the concert and Levon Helm sings lead on “Up on Cripple Creek,” the group's only other Top 40 song and a great tune off their second album, The Band – also known as The Brown Album – released in 1969. I didn't catch it until recently, but Helm mixes up some of the verses. Music promoter Bill Graham, who owned the Winterland, filmed the entire show in black and white, which lasted more than four hours and can be seen here. It shows Helm getting most of the verses correct. I can only speculate that Scorsese must have edited the song for the movie. It's also interesting to note that after the concert was done, The Band went into the studio to made changes to a number of songs – to correct missed or sour notes or to fill in music not picked up by microphones.

Scorsese asks Robertson, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel about the history of the group with Robertson doing most of the talking. It's obvious Manuel was pretty high as he comes across as being out of it, and does at least one interview lying on a couch. Next up we see Manuel singing “The Shape I'm In,” which is ironic as he's not in great shape. A cameraman picked him up perfectly with a spotlight and then it's quickly to a wide shot and then to Danko and Robertson, before returning briefly to Manuel, who does a great rendition of the song.

The first guest on the stage is Ronnie Hawkins, who recruited all five members as his band during the early 1960s. He sings Bo Didley's “Who Do You Love?” and leaves the stage before the song ends.

The film flips back and forth between the concert and the interviews. Robertson, Danko and Manuel talk about stealing food from a supermarket when they first started, as they had no money. While the other two talk, Robertson jumps in to finish the story, and we head back to the stage to hear Danko sing “It Makes No Difference,” his first in the movie on lead vocals. We also get a Garth Hudson sighting as he does a great sax solo. But we can't forget Robbie. He gets the spotlight treatment for a guitar solo on the song.

Other guests come out to sing, including Dr. John doing “Such a Night,” and Neil Young singing “Helpless.” Young's performance is memorable for two things: the one we hear and the one we don't see. What we don't see is cocaine hanging out of Young's nose – digitally removed in post-production. You have to pay attention, but as Young gets on stage, he tells Robertson, “Thank you for letting me do this.” Robertson responds: “Oh, shit, are you kidding? Are you kidding?”

Joni Mitchell does some impressive background vocals, but when the camera pans to her, she's largely in the dark. The reason? The thought was to not have her visible – though we can clearly hear her distinct voice and make out her distinct face – as she would perform later with The Band and if people saw her, it would ruin the surprise. It doesn't make much sense, but everyone was high so that probably played a part in the strange decision.

Joni Mitchell does some impressive background vocals, but when the camera pans to her, she's largely in the dark. The reason? The thought was to not have her visible – though we can clearly hear her distinct voice and make out her distinct face – as she would perform later with The Band and if people saw her, it would ruin the surprise. It doesn't make much sense, but everyone was high so that probably played a part in the strange decision.

More Robertson on not being on the road anymore and a great version of “Stage Fright” by Danko follows. We are then treated to the best interview segment of the movie and it comes from Manuel. He talks about the name of the group, saying in the late 60s that band names were strange. He makes up a couple of great psychedelic band names: “Chocolate Subway” and “Marshmallow Overcoat.” The members wanted the group to be called “The Crackers” or “The Honkies,” but no one else liked it. They were working with Dylan in and near Woodstock, New York, at the time they were searching for a name. Everyone referred to them as “The Band,” and the name stuck, Manuel says.

The film suddenly cuts to an MGM sound studio in Los Angeles in what many people say is the best part – The Band joined by the Staple Singers doing “The Weight.” Simply put: it is spectacular, and the way it is filmed is remarkable. Helm sings the first verse with the Staple Singers not shown. We see Robertson and Danko up front and that Manuel and Hudson have switched places with Manuel on organ and Hudson on piano. We then see Mavis Staples (their last name is Staples, but the band name is singular) taking the second verse and about halfway through it, the camera goes wide to show her sisters and father. Pops Staples singing the third verse, Danko the fourth verse as he did on the original with everyone harmonizing on the final verse. (See it for yourself.)

The song itself is often mistaken for having a religious subtext as it takes place in Nazareth with characters named Luke, who's waiting on the Judgment Day, as well as Moses and the Devil. But it's actually about a town in Pennsylvania where Martin Guitars are still made to this day, and the strange people The Band knew there. The group performed the song during the concert, but it was replaced in the movie by the version done with the Staple Singers.

We get a little bit of Danko, Manuel and Robertson informally singing “Old Time Religion” off stage and off key followed by “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” one of The Band's better-known songs. This version with great horns is one of the best concert songs in cinematic history. Here it is.

Two of the more controversial segments follow. The first is Neil Diamond singing “Dry Your Eyes.” He's great and I'm a longtime fan, but the only connection he has to The Band is that Robertson produced Diamond's album Beautiful Noise earlier in 1976. As Diamond finishes, Robertson says, “Great song,” which is funny because he co-wrote it with Diamond.

The second one has Scorsese asking about groupies when The Band toured. Manuel says, “I love them. That's probably why we've been on the road … not that I don't like the music.” Helm, visibly upset at the question, says to Scorsese, “I thought you weren't supposed to talk about it too much.” He then tells the director to talk about something else.

Back on stage, we get a couple of blues numbers. The first is “Mystery Train” by Paul Butterfield, followed by a killer performance of “Mannish Boy” by Muddy Waters with Butterfield playing the harmonica. Helms later wrote in his autobiography about how angry he was that a Vegas-style Diamond performed while he had to fight to get a spot on the show for Waters, who was a major influence on the group's members.

This section of the film features guest performers, including Eric Clapton, who does “Further On Up The Road.” As Clapton is playing the start of the song, his guitar strap falls off. He calls out “Rob” and Robertson immediately plays the lead perfectly without missing a note until Clapton is ready to resume. (It took me about a dozen viewings to recognize what happened.) The film returns to the MGM sound stage for Emmylou Harris singing “Evangeline,” a fantastic song Robertson wrote shortly before filming of the movie began. He plays electric guitar with Danko on violin, Helm on mandolin, Hudson on accordion, and Manuel on drums.

Back at Winterland, we get snippets of Hudson's brilliant organ playing on “Genetic Method” and “Chest Fever,” the latter is one of my favorite songs by the group. Robertson talks about Hudson's talent and how he was a classically trained musician. When The Band started they each had to pay Hudson $10 a week for lessons. Hudson couldn't tell his family he was in a rock-and-roll band so he said he was a paid music instructor. The Band play another great song, “Ophelia.”

Van Morrison, wearing a ridiculously-tight jumpsuit showing his expanded belly, is the second to last guest performer and he does an inspired version of “Caravan.” To end the cavalcade of stars is the biggest one of them all: Bob Dylan. There were problems with Dylan who only wanted two songs filmed because of a concert movie he was making. (Details of that to come later.)

The film's Winterland concert finale is “I Shall Be Released,” a beautiful song written by Dylan during The Basement Tapes era when he and The Band were in upstate New York. The song, with Manuel singing lead, is the final track on the group's 1968 landmark debut album, Music From Big Pink. Dylan released a version with a different tempo in 1971 on the second volume of his “greatest hits” collection.

The filming of the song is a mess with Manuel singing the second verse, but he's not shown; perhaps Scorsese's cameramen were in poor positions. Hawkins is on stage, but nowhere near a microphone so he is just sitting there. It's weird to see Diamond sharing a stage with Young, Morrison and Dylan. It's the end of the movie at the Winterland, but as Graham documented and as shown on The Last Waltz DVD, there was plenty more to follow, including two jam sessions. The quality of music on the jams isn't spectacular, but it's fascinating to see The Band, without Manuel, play with Ringo Starr, Ron Wood, Neil Young, Dr. John, Paul Butterfield and Eric Clapton.

The film's final interview is with Robertson who talks about life on the road and how you don't want to “press your luck.” He adds: “The road has taken a lot of the great ones: Hank Williams, Buddy Holly, Otis Redding, Janis (Joplin), Jimi Hendrix, Elvis. It's a goddamn impossible way of life.” It would also take Manuel and to a certain extent Danko and Helm.

The film closes on the MGM sound stage with Hudson on organ, Danko on stand-up bass, Robertson on a 12-string, Helm on mandolin and Manuel on slide guitar playing a new instrumental, “Theme From The Last Waltz.”

When The Band played their last concert, beautifully captured by Scorsese, the group was not leaving on top despite what the movie leads you to believe. While the five-man group was extraordinarily talented, they had become a nostalgia band by 1976. Any success they had in 1974 and 1975 was largely due to Dylan, who used them as his backing band at various high points during his career. The Band released two albums in 1975: Northern Lights – Southern Cross with a few good songs, and The Basement Tapes, which consisted of music made with Dylan primarily in 1967. A year earlier, they toured with Dylan, and played on his Planet Waves record. Except for the modest success of Northern Lights, The Band had done little of note on their own since 1970, when their third album Stage Fright was released. They were never able to recapture that brilliance again. By the time of their breakup, The Band was largely irrelevant in an industry that focused on disco and punk, and shunned many 1960s performers.

By 1976, Robbie Robertson, their guitarist and main songwriter, wanted the group to stop touring, and work only in the studio. That worked for The Beatles for a few years, but The Band wasn't The Beatles, and while the Fab Four's concerts were about 30 to 45 minutes long, The Band typically played for a couple of hours. Robertson's idea was ill conceived and the rest of the group objected.

First, the other four members made most of their money touring. After Music From Big Pink, songwriting credits for original compositions were largely attributed to Robertson, despite objections from some of the others, primarily Helm. That meant that the big residual checks and publishing bucks went to Robertson. For the other four, the real money was in touring. As talented as Robertson was as a songwriter, he had dry spells, most notably between 1971's Cahoots and 1975's Northern Lights. It was so bad that the only studio album they released between those two was Moondog Matinee, a mediocre 1973 album of all cover songs.

But Robertson was insistent about not touring, and he expressed that repeatedly during the interview segments with Scorsese in the film. Though the rest of the group balked at the idea of quitting the road, Robertson somehow convinced them to break up in an elaborate show, which became The Last Waltz.

It turned out that Robertson was correct about the dangers of life on the road: The Band reformed in 1983 without him. Manuel, whose hard living as a member of The Band concerned Robertson, committed suicide in 1986 after a small show in Florida. He was 42 years old. Danko, who battled drug and alcohol addictions, died in 1999 after a tour at the age of 56. Helm, also a hard drinker and a chain smoker who battled addictions, made it to 71 before dying of throat cancer in 2012.

The Last Waltz, filmed on Thanksgiving 1976 didn't hit theaters until April 26, 1978. It sat around that long for two reasons: Scorsese was busy with other films, including New York, New York, and Dylan negotiated a delay in order to have Renaldo and Clara, a nearly four-hour concert/documentary/dramatic vignette film from his 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue tour, come out first. Renaldo premiered Jan. 25, 1978, and was a complete flop.

Scorsese was an unusual choice to direct, as he had never filmed a concert or documentary film before. He got the job because Jonathan Taplin, The Band's manager during their heyday, had produced Mean Streets, which Scorsese directed, and recommended him to The Band. Robertson and Scorsese, the latter had a cocaine abuse problem at the time, hit it off well, and developed a friendship and business relationship during and after filming. The other members, except for Danko, showed little interest in making any decision about the movie. It was the bond between Scorsese and Robertson that influenced the film's final product. The movie makes it look like the guitarist-songwriter was the leader despite the fact that Helm, Manuel and Danko sang 99 percent of the group's songs, and Helm had been the unofficial head dating back to when they were called Levon and the Hawks. Robertson doesn't sing lead on any song during the concert and did so on less than a handful of numbers during the group’s recording career. I don't object to top billing for Robertson (who ended up with a producer credit for the film). But Helm bitterly wrote in his autobiography that the movie makes it look like the four others are Robertson's sidemen.

While the film has some shortcomings such as choppy editing, too much of a focus on Robertson and not enough on the great music, it still makes for incredible viewing. At slightly less than two hours in length, it would have been even better had Scorsese added another hour. Woodstock is clearly the best rock film ever made, but The Last Waltz is right up there with Concert for Bangladesh for the second best. The Band’s performances showed why they were so widely respected for their talent and songs, particularly on their first three albums, and why people wanted to see them in concert. The guest performers don't disappoint, either, which is why this is an ideal film for the rock aficionado.

February 9, 1964: The Day the World Changed Forever

By Jon Gallagher

I recently wrote about remembering the Kennedy assassination that took place 50 years ago. It bothered me a little bit that I could actually remember something that happened 50 years ago. But I understand something that had such an impact on history could do just that. It stood out because of its significance. Most of those who were involved with that day are now gone themselves.

That’s why this next memory goes even further to make me want to break out the Bengay and WD-40.

February 9, 1964; exactly 50 years ago today. It was a Sunday. I was sicker than a dog. I was so sick that I missed Sunday school for the first, and probably only time, during my childhood. My older brother came home with some news he thought I might be interested in hearing. Since he was 13 years older than me, he heard stuff that I didn’t have a clue about.

“Be sure and watch The Ed Sullivan Show tonight,” he told me. “He’s going to have a band from England on.”

By the time Sullivan made it to the airwaves, I was feeling much better. I remember gathering around the dilapidated old black and white set that we had (the show was broadcast in black and white so having a color set wouldn’t have mattered one bit) with my mom, dad, sister and I believe my brother dropped by as well.

What I remember is quite different from what actually happened. Or maybe what happened was so much different than what had ever happened before that we weren’t used to it yet. Thanks to YouTube, I’ve seen footage of that broadcast and thank goodness for being able to see it again.

What I remember is that they were introduced and we saw these four guys, jumping around the stage, shaking their heads, and gyrating, their long hair flying all over the place as they screamed into mics over the din of teenage girls who were screaming their lungs out. I remember my dad walking out of the room shaking his head. I remember the Beatles singing something about “Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

In reality, Sullivan introduced the Beatles, the teeny-boppers screamed, and the Beatles did a song called “All My Loving,” a song that was pretty tame, even by the standards we’d seen early in the rock era. The four mop tops didn’t have hair that was long and wild; it was simply combed down over their foreheads rather than having it plastered down with “greasy kid stuff.” Their earlobes, in fact most of their ears, were showing. They wore matching suits and ties, had two guitars, a bass, and a drum kit, and they all smiled while they sang.

And they turned the country on its ear.

The second song they did was “She Loves You,” the song that did have the “Yeah, yeah, yeah” in it. Watching it today, I find the vocal harmonies amazing, something neither of my parents seemed to notice 50 years ago.

The next day at school, the Beatles were the only thing anybody wanted to talk about. Little boys, like me, might have been sent to school with their hair combed back, but it got combed down as soon as I hit a restroom. Suddenly, you couldn’t go anywhere without seeing young boys copying one of the four.

Someone made a boatload of cash on their marketing too. I had forgotten how much went into all the Beatle memorabilia that came out at the time until I started doing some research. I remember having a lunchbox with John, Paul, George and Ringo on it. Here were pencils and notebooks, dolls, plastic guitars and plastic drumsticks. Four or five record labels had demo tapes that the Beatles had sent to then and every one of them were producing 45s as fast as their factories would press them because fans, both male and female, were buying them faster than the record stores (anyone remember them?) could put them out.

In my life since, I’ve tried to always appreciate the music my two older daughters enjoyed. I even took them to an 'N Sync concert once, and found that I probably enjoyed it as much, if not more, than they did! It would be years before my dad finally came around to appreciating their music (I caught him humming “Let It Be” once not knowing it was a Beatles’ song). That night, 50 years ago on The Ed Sullivan Show, was the defining point in the generation gap for me.

Yuletide Songs from the Celluloid

By Steve Herte

Every year radio, department store speakers and television greet the holiday season with the familiar songs and carols to get us in the spirit. But isn’t a song the same as a carol? Not quite. The original definition of a carol is a “round dance;” carols were meant to be danced. The secondary meaning involves the religious joy involved in a carol. Anything else is just a secular holiday song. Even though several carols are played in various movies, we’re just going to investigate popular Christmas songs associated with movies through time and explore a little of their background.

“White Christmas” (1942): from Holiday Inn (1942) and its loose remake, White Christmas (1954). Written by Irving Berlin, it’s the oldest song in my list, and one of the most famous, returns every year to the television screen. Even though the song premiered a year before on “The Kraft Music Hall” radio show, it is more closely associated with Bing Crosby’s unforgettable crooning in Holiday Inn, for which it won the Best Original Song Oscar in 1943.

“Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” (1944): It was made famous by the movie Meet Me in Saint Louis (1944), directed by Vincent Minnelli. It stars Judy Garland as Esther Smith and, as her three sisters, Margaret O’Brien (Tootie), Lucille Bremer (Rose) and Joan Carroll (Agnes). Set in the year before the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, the girls learn that their father is being transferred to New York and the family has to go with him. But they’re eagerly anticipating the fair. The scene is Christmas Eve and Esther is trying to cheer up her sister Tootie. However, the original lyrics are not that cheerful, with phrases as “hang a shining star upon the highest bough,” and “Let your heart be light. Next year all our troubles will be out of sight.” The line “Until then we’ll have to muddle through, somehow,” gave the song a sad melancholy tone to fit the movie scene, and “It may be your last. Next year we may all be living in the past” were an intrinsic part of the story.

In 1957, Frank Sinatra had lyricist Hugh Martin change the words to the ones we know now.

“Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (1949): This familiar holiday tune, based on a popular children’s book by Bob May, was recorded by Gene Autry, who made it into a huge hit. The song first made its film appearance in a Jam Handy Organization cartoon, which was also the last from the Fleischer Studios. The most popular version of the book – and song – is the 1964 stop-motion animated television special. Since Autry introduced the song in 1949, it has become the top-selling song of all time for the season and one of the most familiar to children.

“Frosty the Snowman” (1950): This song, written by Walter “Jack” Rollins and Steve Nelson, is associated most with the television special of same name and sung by Jimmy Durante in 1969. Gene Autry introduced the song on record back in 1950. UPA Studios animated the story of the song explaining how a snowman suddenly became alive by virtue of a magic stovepipe hat as a cartoon in 1954, but the most popular adaptation of the song is the 1969 animated television special from Rankin/Bass Productions.

“Silver Bells” (1950): Originally, the title was “Tinkle Bells” until the double meaning of tinkle was discovered. Whoops! Written by Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, it was sung by Bob Hope and Marilyn Maxwell in the movie The Lemon Drop Kid (1951), directed by Sidney Lanfield and Frank Tashlin. Rumor has it that it was inspired by all the sidewalk Santas and Salvation Army workers on the streets at Christmastime.

“Snow” (1953): Also written by Irving Berlin, it was composed before being featured in White Christmas (1954) with Bing Crosby and Danny Kaye. Originally called “Free,” it had nothing to do with snow. But in the movie it’s a triumphant moment for the winter resort inn at a crucial instance.

“Santa Baby” (1953): This sensual song, written by Joan Javits (niece of Jacob Javits) and Phil Springer, was a big hit for Eartha Kitt and has been heard in Driving Miss Daisy (1989), Elf (2003) and Boynton Beach Club (2005). Miss Piggy also performed it in It’s a Very Muppet Christmas Movie (2002) television special.

“Christmastime is Here” (1965): From the animated television special A Charlie Brown Christmas, it’s a haunting modern song, written by Lee Mendelson and Vince Guaraldi, in minor key, sung by the cast and reprised on piano several times in the film. The melancholy tone of the song reflects Charlie Brown’s mood when he sees everyone enjoying the season without him.

“Welcome Christmas” (“Fah Who Foraze, Dah Who Doraze”): from the television special How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1966), directed by Chuck Jones. With lyrics by Dr. Seuss and music by Albert Hague, it was sung by Cindy Lou Who and all of Whoville while they linked hands around the town’s Christmas tree. Boris Karloff narrated the film and supplied the voice of the Grinch. Hague was born to a Jewish family in Berlin but was raised as a Lutheran to avoid Nazi persecution. He also wrote the music for “You’re a Mean One Mr. Grinch”, “Young and Foolish” and several songs for the TV series Fame. “Welcome Christmas” is the song that cues the change in the Grinch’s heart.

“We Need a Little Christmas”: from Mame (1974, originally entitled My Best Girl), music and lyrics by Jerry Herman. The story is based on the 1955 Novel “Auntie Mame” by Patrick Dennis and is a musical remake of the 1958 film of the same name starring Rosalind Russell. Mame starred Lucille Ball in the title role, with Beatrice Arthur as her best friend Vera Charles. Mame loses her fortune in the 1929 stock market crash and uses her unsinkable style to bolster up the spirits of those around her by celebrating Christmas early (only one week past Thanksgiving Day). Even though the bouncy beat of the song suggests dancing, it is not considered a carol. The up-tempo is meant to brighten a rather dark period in American history.

“Somewhere in My Memory”: Written by John Williams with lyrics by Leslie Bricusse for the soundtrack of Home Alone in 1990 and Home Alone 2- Lost in New York (1992), directed by Chris Columbus. A children’s chorus sets the sentimental mood for a child accidentally left home (and in the Plaza Hotel) on Christmas Eve by his way too distracted parents and dozens of relatives. The lyrics reflect his situation and his longing.

“Believe” (2004, from The Polar Express): Written by Glen Ballard and Alan Silvestri and sung by Josh Groban, it won a Grammy in 2006 for Best Song Written for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media. The riotous train trip to the North Pole (including a scary scene where the entire train is off the tracks and skidding on ice) is instrumental in helping a child believe in Santa and all things miraculous as the lyrics say: Believe in what you feel inside, And give your dreams the wings to fly. You have everything you need. If you just believe.

“What’s This?”: From The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993, written and sung by Danny Elfman) as Jack Skelington is suddenly transported from the land of Halloween to Christmastown. He’s agog at all the strange sights and colors and investigates every nook and cranny. His amazement shows in the lyric:

There are children throwing snowballs here instead of throwing heads,

They're busy building toys and absolutely no one's dead

He later takes over the job of Santa Claus and mixes the chaos of Halloween into the peace and calm of Christmas.

“The Most Wonderful Time of the Year” (1963): This lively swing waltz was written by Edward Pola and George Wyle and recorded by Andy Williams that same year. Though it’s a waltz, it’s still not a carol. It was featured in the Hallmark Hall of Fame television movie of the same name starring Henry Winkler and Brook Burns in 2008.

Yes, for me it truly is the most wonderful time of the year. Wars stop temporarily for it, people think more of others than themselves and some of the most familiar and beloved songs are sung in every venue. I know there are more movies with holiday songs and even more featuring carols with new melodies being written every year. My intent here is to start the spark of memory. It’s now your assignment to supply your own list.

James Bond: The Man and His Music

By Steve Herte

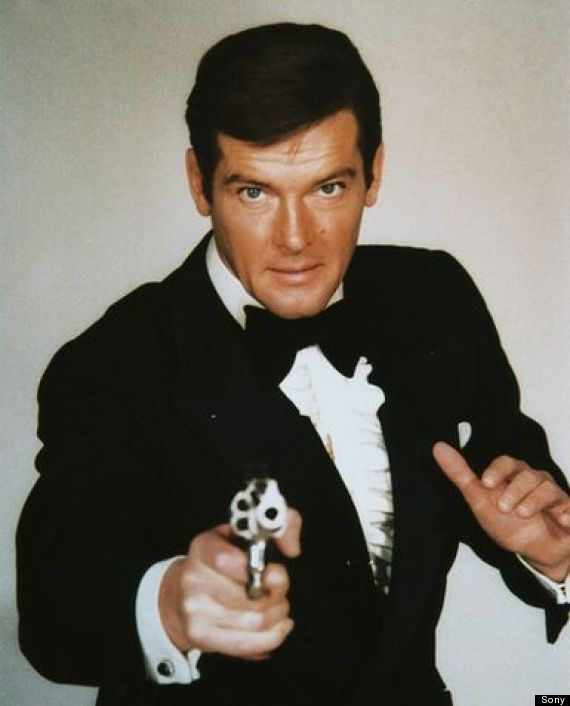

It was fifty years ago that the first James Bond movie Dr. No was released with Sean Connery as the suave, international spy based at MI6 in London. Ursula Andress became the first “Bond Girl” in her role as Honey Ryder, and Monty Norman wrote the signature “James Bond Theme” with its characteristic guitar riff as performed by John Barry and his Orchestra. It was the only one of the 24 Bond movies (Yes, I count Never Say Never Again) with a totally instrumental theme song. Since then, I have been collecting the Bond themes both on records and karaoke discs. Why? I find them exciting pieces of music with interesting, sometimes complex melodies and therefore a challenge to sing. So, if you will, let’s take a musical journey through time with James Bond.

It’s 1963 and the movie is From Russia with Love. Again, Connery stars and we have two Bond Girls, Eunice Grayson as Sylvia Trench and Daniela Bianchi as Tatiana Romanova. Lionel Bart (responsible for music in the Broadway musical Oliver) wrote the title theme, which was hauntingly rendered by Matt Monro. This song made my top five favorites (to be listed at the end of the article).

1964 brought us Goldfinger. Sean is still the man and Honor Blackman is Pussy Galore (Sean had a real problem pronouncing her name), with Shirley Eaton as Jill Masterson. Shirley Bassey belted out the theme song written by Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley. Apparently, she impressed everyone because she’s the only singer to get more than one theme song. She actually did three, as you will see.

Thunderball followed in 1965. Sean is still white hot as Bond, and Claudine Auger is hotter as Domino Derval. John Barry and Don Black wrote the theme song, which was sung by Tom Jones when he could hit the high note at the end without going into his vibrato. (Tom put a lot of passion into this one.)

Nancy Sinatra hung up the boots that were made for walkin’ in 1967 and sang the beautiful theme to You Only Live Twice, again written by Leslie Bricusse and backed by cascading violins. It was Sean’s fifth movie and Akika Wakabayashi was Bond Girl Aki. If I had to choose the easiest Bond theme song to sing, this would be one of them.

Then, in 1969 came In Her Majesty’s Secret Service with Barry handling the theme song’s music and Hal David writing “We Have All the Time in the World” for Louis Armstrong to perform. This song pretty much went unnoticed because of Sachmo’s rendering, but when I bought the sheet music and played it at home on my Hammond it became an instant favorite. It was an, “Oh that’s what it really sound like!” moment. George Lazenby did his only performance as Bond in this movie and the wonderful Diana Rigg was Bond Girl Teresa Bond.

We’re back to Connery in 1971 when Diamonds Are Forever hit the big screen and we saw Jill St. John as Tiffany Case and Lana Wood as Plenty O’Toole. Shirley Bassey returns to perform the sultry theme song sounding as if she learned some song styling from Eartha Kitt. But as the song progresses, there’s no doubt that it is Shirley singing. The team of Barry and Black once again wrote a great song.

The first of the Roger Moore James Bond movies airs two years later in 1973: Live and Let Die. We now see a different, more mischievous, rather than sardonic, Bond. Once again we have two Bond Girls – Jane Seymour as Solitaire and Gloria Hendry as Rosie Carver, and for the first time we have a rock and roll band, Paul McCartney and Wings alternately crooning and hammering out the theme song. I imagine this song became popular because it was easier to sing than “You Only Live Twice” (that and considering Paul’s popularity with the ladies).

The team of Barry and Black return in 1974 with the theme to The Man with the Golden Gun sung vivaciously by Lulu. Moore stars again with Britt Ekland as Mary Goodnight and Maud Adams as Andrea Anders. Even though this movie was produced in the “Disco” Seventies, the theme song harks back to the Go-Go Sixties – and Lulu was perfect for that.

After three years without a Bond film, 1977 gave us The Spy Who Loved Me. Moore is once again at the helm with Barbara Bach as Anya Amasova. The great Carly Simon took the theme written by Marvin Hamlisch and Carole Bayer Sager and made it a soaring love song to Bond.

Two years later in 1979, Bond (Moore) goes into orbit with Moonraker and we once again have two Bond Girls: Lois Chiles as Holly Goodhead and Corinne Cléry as Corinne Dufour. Barry and David are back together again to create the third theme that Shirley Bassey takes off with and flies to the ionosphere and back.

Two years later and For Your Eyes Only is produced (1981) featuring Moore in his fifth appearance and Carole Bouquet as Melina Havelock, with Lynn-Holly Johnson as Bibi Dahl (great name). The airy and clear tones of Sheena Easton are heard singing another one of my favorite themes written by Bill Conti and Michael Leeson with a wonderful piano background.

A pattern seemed to have developed of a Bond film every two years when in 1983 the impossible happened. Two films in one year! The first, Octopussy with Moore as Bond and Adams reappearing as Octopussy had a theme song written by Barry. However the song “All Time High,” was much better and sung beautifully by Rita Coolidge.

The second movie, Never Say Never Again, has been vilified as “never should have been made.” It was Connery’s seventh (and last) appearance as Bond and featured Kim Basinger as Domino Petachi, with Barbara Carera as Fatima Blush. The great Michel LeGrand wrote the theme to this unfortunate movie and it was performed rather lack-lusterly by Lani Hall. It is a good song, but just not performed in the exciting Bond style.

The two-year pattern is back in 1985 when A View To A Kill gave Roger Moore his seventh, and last, Bond role. It also had the debut of the first black Bond Girl: Grace Jones as May Day. The other Bond Girl, Tanya Roberts as Stacey Sutton, is almost eclipsed by her. (I’ll never forget when May Day parachutes off the Eiffel Tower.) The pop group Duran Duran created and banged out the title song. Though I’ve tried singing this one, I find the melody still escapes me.

1987 saw the showing of The Living Daylights, marking the debut of Timothy Dalton as Bond. Our Bond Girl is Maryam D’Abo as Kara Milovy. Barry returns to do the theme song, which is performed by pop group A-ha, but two other songs beautifully done by Chrissie Hynde and the Pretenders shine much brighter: “Where Has Everybody Gone,” and the wonderful love song, “If There Was A Man.”

Dalton performs as Bond for the second and last time in 1989 in the movie Licence To Kill, and Carey Lowell (remember her in Law and Order?) as Pam Bouvier is the Bond Girl. Gladys Knight lends her inimitable style in singing the theme song written by Narada Michael Walden, Jeffrey Cohen and Walter Afanasieff. It’s a perfect vehicle for her vocal talents and she does a great job.

Six years pass (1995) before GoldenEye allows Pierce Brosnan to try his hand at the leading role (frankly I think he’s too pretty to be a believable Bond, but he is suave). Famke Janssen plays Xenia Onatopp (another great name) and Izabella Scorupco is Natalya Simonova. If you can catch the video online of Tina Turner cranking out the slinky, sexy theme of this movie written by Bono, do it. It’s worth it.

The pattern is back in 1997 with Tomorrow Never Dies and Brosnan is back with Terri Hatcher as Paris Carver and the gorgeous Michelle Yeoh as Wai Lin. One of the most difficult and least familiar theme songs is the one from this movie written and performed by Sheryl Crow and co-created by Mitchell Froom. It’s an excellent song with lots of echo and formidable sounding violins.

In 1999, The World Is Not Enough brings Pierce to the screen for a third time and, for the first time, there are three Bond Girls: Serena Thomas as Dr. Molly Warmflash, Sophie Marceau as Elektra King, and Denise Richards as Dr. Christmas Jones (I love the Bond Girl names!). Shirley Manson of the rock group Garbage sings a very, very traditional-sounding Bond Theme song written by David Arnold and Black; one that almost harkens back to the beginning.

Three years later in 2002, Brosnan gets his last chance to play Bond in Die Another Day, flanked by Halle Berry playing Jinx Johnson and Rosamund Pike as Miranda Frost. Madonna uses her baby-doll voice, electronic vocals and rap to perform by far the second least traditional and melodic theme written by herself and Mirwais Ahmadzaï. In fact, this theme repeats the title more than any other lyric. The meager verses seem unimportant, but it’s great for dancing.

The remake of Ian Fleming’s first Bond tale, Casino Royale is Daniel Craig’s first Bond role in 2006 with Eva Green as Vesper Lynd and Caterina Murino as Solange Dimitrios. Craig is an edgier, down-to-Earth Bond with a no-nonsense attitude that would have made author Fleming proud. Add to that the equally edgy and much more traditional song, “You Know My Name” belted out by Chris Cornell and written by him as well with Arnold. For some reason, however, Casino Royale doesn’t have a title song.

Craig’s second Bond movie, Quantum of Solace (2008), pairs him with Gemma Arterton as Strawberry Fields (you have to love that) and Olga Kurylenko as Camille Montes. Being the second movie in a row without a title theme, Quantum of Solace has a song, “Another Way To Die,” written by Jack White and performed in a duet with Alicia Keys. It emanates the Bond feel in excitement and passion but ranks least in melodic content (it’s mostly on one note).

Finally, four years later (2012) comes the most recent Bond film Skyfall, starring Craig again with Naomie Harris as Eve and Bérénice Marlohe as Sévérine. The title theme song is a masterpiece written by Paul Epworth and Adele and sung beautifully by Adele (definitely destined to be an Oscar award winner). The dynamics, the melody, the background and Adele’s impassioned vocals make it perfect.

I know I promised you my top five songs. Here they are:

1. We Have All The Time In The World

2. Skyfall

3. Nobody Does It Better

4. For Your Eyes Only

5. From Russia With Love

I was surprised at how wonderful Skyfall was and how high it immediately placed. I’m still learning the post-1985 songs for future karaoke sessions and I’m hoping this little journey has put the 50 years of James Bond movies in a new light for you. Maybe you’ll even notice how the music in other films add to the mood as well.

Barbershop 101 and a Surprise at Carnegie Hall

By Steve Herte

Those who know me know that I love to sing. Over the years I have sung at Karaoke bars, in a formal chorus, and in a couple of barbershop quartets, including one with my beloved late girlfriend (who possessed one of the most angelic voices I have ever heard).

Barbershop is one of only two uniquely American forms of music. (Sorry rappers, but Rap is neither music nor uniquely American. Africans have been rapping long before it was popular.) The other is Jazz. Its roots go back to the 1800s when the Tonsorial Parlor (Barber Shop) was the place for men to gather, smoke cigars, and converse as well as be groomed. Once four men were gathered one would start a melody and the others would improvise the three other parts, one above the melody, one below and one to create the unique sound of a barbershop quartet whose part weaves both above and below the melody. This original form was later dubbed “woodshedding,” probably because, when not in the Barber Shop, this was where the men took the oft times rough-shod music in politeness.

Although very popular in the early part of the 20th Century, barbershop music lost its luster with the coming of the 20s, replaced by Jazz and a faster pace of life.

The revival of this truly American art form took place in 1938, in Tulsa Oklahoma. It was there that O.C. Cash organized the S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. (the Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America) with a double goal: to standardize, preserve the style, and promote the form of music, and have the most impressive and longest organizational title. The society grew over the years and several quartets formed until a competition was organized to find the best. A judging system was established to measure how well the standards of the style were being executed. Chapters formed all over the United States and choruses formed to facilitate the formation of quartets and give the less extroverted singers a medium to participate in the style. Soon the choruses became so proficient that they too entered competition. Choreography was added to the performance and became a category in the judges’ training.

Has barbershop singing ever been in the movies? Sad to say, to the best of my knowledge, only two movies featured barbershop harmonizing. The first was the Judy Garland-Van Johnson musical about turn-of-the-century America, In The Good Old Summertime (1948). George Boyce, Eddie Jackson, Joe Niemeyer, and Charles Smith teamed to sing the barbershop classic “Wait Till the Sun Shines, Nellie,” and also joined star Judy Garland for the delightful “Play That Barbershop Chord.” The second movie to feature barbershop harmonies was The Music Man (1962), where a barbershop quartet forms an integral part of the story. The Buffalo Bills, 1950 International Quartet Champions, who had appeared in the Broadway production, reprised their role in the film and sang “Lida Rose,” a favorite of barbershop quartets.

When I joined in 1973, there were chapters in England and Canada. Over the 35 years, I sang in two choruses, directed one and participated in at least 15 quartets as tenor and the society expanded to Scandinavia, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Holland and Russia. The style became second nature to me. The song has to be easy to sing, follow a progression called the “circle of fifths,” have a chord on every note and those chords must be predominantly (about 75%) minor seventh chords (the “barbershop seventh”). The structure of these chords should form around the melody singer (the Lead) and the combination of bottom note (Bass), middle note (Baritone) and Lead note should generate the top (Tenor) note, so that when the tenor sang that note the chord would “ring” (generate over-tones) above the tenor part. This four-part ring is what distinguishes Barbershop from Doo-Wop (usually only three parts) and swing (five or more parts) and classical SATB (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass) where the melody is usually in the top part. Major seventh chords are verboten (not encouraged) and diminished or augmented chords are only allowed as transitional chords (those leading to key or root chords) and never when the melody is on the seventh.

On

December 26, I attended the USA-Japan Goodwill Concert

featuring an all-wind instrument orchestra (with the exception of the

percussion section) and a women’s chorus from Japan in the first half and a

young men’s barbershop chorus and two championship barbershop quartets in the

second half. The orchestra was splendid and very impressive, especially when

they finished with “Stars and Stripes Forever.” The women’s group was a smaller

one than last year’s but they were charming and performed songs like “Getting

to Know You” and “Happy Talk” with sensitivity and graceful choreography. Then,

after an intermission the USA side performed.

The No Borders Youth Chorus, Vocal Spectrum, and OC Times were on the USA side. No Borders sang “The Muppet Show Theme” (cute) and “You're A Mean One, Mr. Grinch.” They were introduced with "Can you believe these guys never met each other until tonight?" (And they sounded like they didn't do too much rehearsing together either). Their lack of synchronization made that blatantly obvious. But they did do a passable job on Billy Joel's “Lullaby (Goodnight, My Angel).” The song “Nearer My God to Thee” returned to synchronization problems and featured an unfortunate choice for soloist. Vocal Spectrum sang “When I See an Elephant Fly,” and the Beach Boys' “Good Vibrations.” The first song was, beneath their talent and silly (basically a vocal exercise) - I couldn't understand any of the words except the title (Usually the words are paramount to understanding the message of a Barbershop song). The second was ruined by the tenor singing the electronic (don't they know nobody sings that?) high part on every chorus, just because he could. OC Times sang “I'm Walkin',” a little too fast and once again incoherently. Then a song called “Unbelievable,” which was mostly scat and incomprehensible words, except for the title. After I heard it I turned to my friend and asked, "What the heck was that?" Then both quartets joined the chorus in the song “Higher and Higher.” Man, that's Barbershop, NOT! I was wondering why I stayed.

Knowing this strict structure and realizing that the style must evolve in order to survive, I’m still wondering why some singers ignore one for the other. Also realizing that the only “professional” Barbershop quartets were the Chordettes (Mr. Sandman) and the Osmond Brothers when they were discovered by Andy Williams, I understand that the hobby (some think it’s a lifestyle) is mostly amateur. But, in an august venue such as Carnegie Hall, where the crème de la crème of Barbershop have performed in the past, why should such songs and such performances be posing to represent the style when they obviously are not? Maybe I’ve been spoiled. But I do know that when Barbershop is properly sung it is thrilling not just for the audience, but for the singers themselves. That’s why I’m always ready for my quartet reunions.

This is Spinal Tap & Anvil! The Story of Anvil

By David Skolnick

Editors’ Note: We’re always looking to branch out, which leads us to a new feature. Message in the Music is about films in which music plays a significant role, but the movies wouldn’t be considered musicals. It’s kind of a musical non-musical. Unlike West Side Story, Grease, Oklahoma! or an Elvis movie, actors in these films don’t suddenly break into song. That is, unless they’re in bands – real and fake. For starters, I’m reviewing one of my all-time favorite films, and a documentary I recently saw that is pretty funny even though it’s about a real band.

This is Spinal Tap (Embassy Pictures, 1984) – Director: Rob Reiner. Starring Michael McKean, Christopher Guest, Rob Reiner, & Harry Shearer.

I’ve seen This is Spinal Tap close to 50 times, and I’ll likely see it 50 more. This groundbreaking “mockumentary” has some of cinema’s funniest and most clever lines – and many of them were ad-libbed. The film tells the story of fictitious aging English hard-rock band Spinal Tap on a tour of the United States in support of its latest album, “Smell the Glove.”

This is Rob Reiner’s directorial debut, playing Marty DiBergi, a documentary director following and filming Tap’s tour. The band’s three main characters are David St. Hubbins (Michael McKean), the lead singer and rhythm guitarist; Nigel Tufnel (Christopher Guest), the lead guitarist; and bassist Derek Smalls (Harry Shearer).

The music plays a key role in the film, with McKean, Guest, Shearer as well as David Kaff, who plays keyboardist Viv Savage, and R.J. Parnell, who plays drummer Mick Shrimpton, all performing.

While the band plays a number of songs in their entirety such as “Big Bottom,” about a woman with a, well, big bottom; “Hell Hole,” “Stonehenge,” and “Sex Farm,” there are snippets of other songs supposedly from years ago when they were somewhat famous. On the DVD, you can see complete performances of several of those songs. The DVD also includes more than an hour of scenes not in the movie, and commentary from McKean, Guest and Smalls in their Spinal Tap characters. The soundtrack is excellent and I highly recommend it. I’ve had the cassette since 1985.

The film has numerous running gags, including the strange and funny deaths of their drummers. One dies in a “bizarre gardening accident” that authorities said was “best (to) leave it unsolved.” Another died choking on vomit – someone else’s vomit. “You can’t really dust for vomit.” And everyone’s favorite: spontaneous human combustion. “Dozens of people spontaneously combust each year. It’s just not really widely reported,” St. Hubbins says matter of factly.

There is a delay in releasing “Smell the Glove” because of the album cover. Bobbi Flekman, an executive with the band’s record company and easily Fran Drescher’s best role (which isn’t saying too much), tells the band’s manager, Ian Faith (Tony Hendra), the cover is “sexist,” and stores won’t stock it for sale.

Flekman tells Faith: “You put a greased naked woman on all fours with a dog collar around her neck, and a leash, and a man’s arm extended out up to here, holding onto the leash, and pushing a black glove in her face to sniff it. You don’t find that offensive? You don’t find that sexist?” Faith responds: “Well, you should have seen the cover they wanted to do. It wasn’t a glove. Believe me.”

(Later, Ian tells the band about the problem with Nigel naively responding, “Well, so what. What’s wrong with being sexy?")

This results in the album being released with an all-black record sleeve with no title or the band’s name to be found. The band is deflated despite Ian trying to put a positive spin on it. Nigel kinds of buys it, saying, “It’s like, how much more black could this be? And the answer is ‘none. None more black.’”

Gigs get canceled, including one in Boston with Faith telling the band, “I wouldn’t worry about it though. It’s not a big college town.” At a show in Cleveland, the group tries to find its way to the stage but gets completely lost. Several real bands have said over the years that’s happened to them. Actually several bands have said a lot of the scenes in the film really occurred and the movie hits a little too close to home.

A big production number with what is supposed to be a replica of Stonehenge for the band’s song of the same name is priceless. Instead of using feet, Tufnel draws the dimensions of Stonehenge on a napkin in inches. Rather than not use the mini-Stonehenge, Ian hires two midgets to dance around the replica with hilarious but embarrassing results. “There was a Stonehenge monument on the stage that was in danger of being crushed by a dwarf.”

Finally, St. Hubbins’ girlfriend arrives, causing Yoko-esque tension between St. Hubbins and Tufnel as well as with Faith, who quits after Jeanine (June Chadwick) is recommended by her boyfriend to be the group’s co-manager. The band is in disarray with the final straw being a gig at an Air Force base that leads to Nigel quitting. The next stop is at an amusement park in Stockton, California, where a puppet show is listed on a sign above the band. Jeanine sees it and says, “If I told them once, I told them 100 times to put Spinal Tap first and puppet show last.”

The best parts are the free-flowing interviews DiBergi does with the three Tap principals as McKean, Guest and Shearer are wonderful improv comedians. Discussing reviews for their albums are highlights. “The review for ‘Shark Sandwich’ was merely a two-word review which simply read ‘Shit Sandwich.’” For the “Rock and Roll Creation” album, a reviewer wrote: “This pretentious ponderous collection of religious rock psalms is enough to prompt the question, ‘What day did the Lord create Spinal Tap, and couldn’t he have rested on that day too?’” “That’s a good one. That’s a good one,” Smalls responds.

The most memorable scene has DiBergi in Tufnel’s house looking at his collection of guitars. One guitar has never been played. Tufnel freaks out when he thinks DiBergi is going to touch it, telling him to not even point or look at it. In the room is an amp that goes to 11 rather than 10. Tufnel goes into an explanation about it being “one louder.” DiBergi asks why not just make 10 be the loudest. Tufnel looks at him completely confused and says, “These go to 11.” Many musicians since then have had amps that go to 11 in honor of the scene.

The film ends with the band getting back together to tour Japan where “Sex Farm” has hit No. 5 on that country’s singles chart. Shrimpton dies on stage, a victim of spontaneous combustion. What are the odds?

The movie is a perfect parody of rock-and-roll excess with great music and excellent acting. Guest, McKean and Shearer have done several other improv films over the years. While many are wonderful, none can touch their first collaboration.

Anvil! The Story of Anvil (Abramorama, 2008) – Director: Sacha Gervasi. Starring Steve “Lips” Kudlow & Robb Reiner.

Around the same time This is Spinal Tap was released, a heavy-metal band, Anvil, was at their peak. In the early to mid-1980s, the Canadian band played at rock festivals with this documentary initially focusing on a 1984 show in Japan that also included Bon Jovi, the Scorpions, Whitesnake and the Michael Schenker Group (though the latter and significantly less successful band isn’t mentioned in this documentary).

While Bon Jovi, the Scorpions, Whitesnake and other/metal bands of the time – including Metallica and Motorhead – enjoyed commercial success, Anvil didn’t. Director Sacha Gervasi, who grew up an Anvil fan and was a roadie during the band’s peak years, frames the film that members of other bands – including Metallica, Motorhead, Guns N’ Roses, Anthrax, Slayer and Megadeath - all greatly admire Anvil and are shocked more than two decades later that the group never made it.

After years of the disappointment and poor sales of 12 albums, Steve “Lips” Kudlow, the band’s singer and guitarist, and drummer Robb Reiner are the only original members left. While they both have mundane jobs - Reiner’s naïve simplicity parallels Christopher Guest’s Niles Tufnel - they haven’t given up their dream of being rock stars. The two other members of the band from the early 80s have moved on, replaced by others.

When you listen to them play, though, it’s obvious why they never reached that top level. Despite the musical shortcomings of Bon Jovi and Whitesnake, for examples, Anvil is even worse. One scene in which Kudlow is in the studio singing is unforgettable as he is terrible. But that’s not the point of the film. Also ignored is that the band made some bad business decisions and Kudlow had an opportunity to play guitar with Motorhead, but opted to stay with Anvil.

Kudlow and Reiner, longtime friends from childhood, have problems similar to Spinal Tap, except Anvil is a real band. Anvil gets booked for a European tour, which turns out to be an absolute disaster. You may feel bad for the band, but you will also find yourself laughing at what happens.

The European tour starts out well with the band playing at the Sweden Rock Festival and they run into Michael Schenker and former Vanilla Fudge drummer Carmen Appice, who comes across as having no idea who they are. (In the mid to late 70s, Appice was Rod Stewart’s drummer and with Rod co-wrote “Da Ya Think I’m Sexy?” and “Young Turks.”) It’s similar to when Tap run into Duke Fame, a famous musician, in a hotel lobby and he doesn’t know who they are.

That festival show is the highpoint of the tour. They get lost in Prague trying to find the bar where they are to perform. At least Spinal Tap got lost inside a concert hall in Cleveland. They show up two hours late, perform to a near-empty audience and get into an argument, that becomes a little physical, with the bar owner who won’t pay them. The band misses train connections, runs out of money, has gigs canceled and when they actually perform there’s hardly anyone there to listen. Reiner is ready to quit and go home, but Kudlow convinces him to stay.

The last show of the tour is akin to Tap’s airbase and amusement park concerts. Anvil plays at a Transylvania show in a 10,000-seat arena. They play in front of 174 people.

“Everything on the tour went drastically wrong. But at least there was a tour for it to go wrong on,” Kudlow says.

Despite one disaster after another, Kudlow and Reiner decide to give it one last shot by hiring the producer of what they considered their best-sounding album. They believe they just haven’t been produced properly and that’s why they keep failing to make it big. But without a record label, they’ve got to come up with the money, about $20,000, to make the album. To raise the money, Kudlow works for a telemarketing company selling sunglasses. It’s an epic failure. His sister, Rhonda, gives him the money. They end up making the album in England and the frustration of the project and decades of failure leave the two of them arguing and Reiner quitting again. Once more, Kudlow convinces Reiner to finish the album.

They love the end result, but can’t get any label to sign them despite sending it everywhere. Kudlow is proud of the record even though no one wants to hear it. Like Spinal Tap, Anvil is asked to go to Japan. They’re under the impression they are to be headliners, but it turns out they are the opening band for a three-day rock festival. They anticipate yet another letdown, but the movie ends on a high note as they get to play in front of a decent and excited crowd.

Based on this film, Anvil received a few opportunities to open for some bigger bands, most notably AC/DC, play some festivals and appear on a handful of television shows.

As a film, Anvil! The Story of Anvil is interesting and shows how much the principals in This is Spinal Tap know about the music industry. The quality of the documentary is excellent, even though it does ignore some of the band’s shortcomings, and you do feel bad for Kudlow and Reiner as they face one obstacle after another. Their misadventures are so tragically funny that you can’t help but laugh at their repeated failures and inability to recognize that they’re never going to make it.

No comments:

Post a Comment