Christine, Ed Garea and

David Skolnick share their top five Francois Truffaut-directed films.

By Christine

When we lost Francois

Truffaut at the young age of 52 from a brain tumor, we lost more than a

director; we lost an artist who climbed to the status of a cultural icon in a

little over a quarter of a century. He was easily the best director France has

had since the days of Jean Renoir (we can only wonder about what sort of career

Renoir would have had if not for the war), and our most prolific in terms of

films that are now acknowledged as classics of the cinema.

There were no limits of

genre for Truffaut; his films range from stark drama to the autobiographical to

romantic comedy to science fiction. A jack of all trades? Yes, and in my

opinion, a master of all. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Truffaut’s films

successfully crossed over to the moviegoing audiences in other countries,

especially America, where foreign directors had long been consigned to an “art

house ghetto.” I think the reason for his success comes from the fact that he

eschews the stridence of the political statement for the emphasis on the

universal human condition. He had famously said that “life is neither Nazi,

Communist, nor Gaullist, it is anarchistic.” For Truffaut, the human condition

comes down to love: the abundance or lack of it; the elation it brings and the

despair it imposes; the difficulty of communication with respect to being in

love; and the resilience of children in the face of the lack of love.

Although many of his

films were autobiographical, he also availed himself of other sources, ranging

from Henry James to Cornel Woolrich to Henri-Pierre Roche. He once said that if

the story was good, did it matter who the author was? That material could not

be in better hands, for he had that rare ability to take such material and make

it his own without compromising the integrity of that original material, a rare

feat for a filmmaker.

I was asked by the

editors to pick my five favorite Francois Truffaut films. Five. Five? A most

difficult task to accomplish when every film he made is my favorite. But, yes,

I suppose it must be five. Hence, beginning with number five, here is my list:

5. Vivement dimanche! (Finally Sunday, or Confidentially Yours, 1983): It was Truffaut’s

last film, and sadly showed why he died all too soon. Keeping with his theme of

love, this is a heartfelt tribute to the movies he grew up with; the movies he

loved. Fanny Ardent is the secretary to businessman Jean-Louis Trintignant.

When he is falsely accused of murder, she sets out to investigate and clear her

boss in this wonderful mélange of film noir and suspense thriller alleviated by

screwball comedy in a style that reminds us of Hitchcock. I loved the name of

the secretary, “Barbara Becker,” a wonderful noir moniker denoting at once the

Hitchcockian relevance – and reverence. Warning! This film should be recorded

rather than seen live, for once viewed, you will want to see it again. When I

saw Woody Allen’s Manhattan Murder Mystery with my husband, we

noticed the similarity between Allen’s movie and Vivement Dimanche! I

shed more than one tear thinking about what Truffaut would have said about it.

4. Les Quarte cents coups (The 400 Blows, 1959): One can do no better in a film debut than

create one of the enduring classics of cinema. The heartbreaking story of

Antoine Doinel’s childhood was based closely on Truffaut’s own childhood. A

realistic, and yet, extremely personal film about Doinel’s troubled childhood,

it’s the very sort of film Truffaut challenged others to make. When I first saw

it, it made me laugh, especially with the school scenes. Later it made me cry,

when his mother abandons him in the reform school with the coldness with which

one might dispose of an old piece of furniture.

3. Le Nuit americaine (Day for Night, 1973): A touching and hilarious look at the

madness that comes with the making of a film. Truffaut stars as Ferrand, a

director filming Je vous presente Pamela (Meet Pamela), the story

of an English married wife falling in love and running away with her French

father-in-law. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Ferrand is beset with problems

large and small, from choosing the right props for a scene to the film lab

ruining an expensive crowd scene to dealing with the actors themselves,

including a leading lady recovering from a breakdown, a co-star more interested

in romancing the script girl than the movie, an alcoholic actress who can’t

remember her lines, and most hilarious of all, a cat that won’t hit his mark.

For me, the beauty of this film is in the genius with which Truffaut put it

together, establishing the difference between Ferrand, the character, and

Truffaut, the director. As Ferrand he shoots Meet Pamela rather unexceptionally with a static camera, but as

Truffaut, filming the behind-the-scenes story, he uses fluid camerawork. Day for Night is a technical term for

night scenes shot during the day with an optical filter, and when we think

about it, it sums up the picture perfectly. If it seems similar to a film

Jacques Tati would make . . . well, Truffaut once confided to me of his

admiration for Tati when I broached the subject. So let us draw our

conclusions.

2. Baisers voles (Stolen Kisses, 1968): This is my personal favorite of the Antoine

Doinel series. Antoine is dishonorably discharged from the army and returns to

Paris, where he finds it difficult to adjust to civilian life. He takes on a

series of jobs, going from a dismal turn as a night clerk at a hotel to working

as perhaps the most improbable private eye in history, to a turn as a

television repairman. For me the beauty of the film lies in its subject matter:

an awkward age that we tend to ignore, one’s early twenties. I think for we

French, the early twenties are more confusing than our teen years because until

then everything is pretty well laid out for us. It’s when we have to assume the

adult life that everything comes crashing down. For me that moment came after finishing

my university studies balancing what it was I intended to do with my life while

dealing with love in the form of a few boyfriends. I generally remained

confused until my mid-20s when I began my career as such and shortly after

that, meeting my husband, who made it all come together, proving that Truffaut

was right about the power of love.

But alas, for Antoine

Doinel, love was never that easy. It is difficult enough when thinking of his

Christine, but when he’s in love with her, she’s not in love with him; and when

she’s in love with him, he’s pursuing someone else. Look for the scene where

Antoine and Christine spend the night, and in the morning he proposes to her

with what looks like a bottle opener substituting for a ring. I think it’s one

of the most beautiful and deeply poetic scenes in cinema history.

1. Jules et Jim (Jules and Jim, 1962): For me, it would take a really remarkable

film to top Baisers voles. This should give the reader an idea of

how remarkable Jules et Jim is. It’s not only Truffaut’s

finest film, but also one I regard as one of the 10 best films ever made. It’s

a riveting story of the love and friendship forged over a span of 25 years

between best friends Jules (Oskar Werner) and Jim (Henri Serre) with the

free-spirited Catherine (Jeanne Moreau). I shall leave it to others to describe

the plot, but the thing I have always found interesting is that the novel upon

which the film is based in an autobiographical one. With this film Truffaut

first begins to examine the very nature of love while creating a mise-en-scene

of the world as a fable. In the first half of the film, as the three friends

experience the joy of love, Truffaut’s camerawork expresses their euphoria. In

the second half, when the three friends are facing disillusionment and loss,

the camera reflects the mood and the film becomes subdued. It seems strange

that a period drama adapted from a novel written by a 75-year old man should

have such resonance with the youth of the time, but Moreau, Werner and Serre

bring an infectious exuberance to their characters. Besides being attractive

and charming, they also defy the conventional morality of society. Catherine is

the epitome of the free spirit, moving freely from one lover to another;

fighting for equality in her own way. Unlike Jules and Jim, who channel their

desires through art, Catherine expresses her talents in the act of living

itself; her essence lies in her very unpredictability. Yet, at the same time

she is searching for love and the security that goes with it. It would seem

that she finds it with Jules, but their temperaments are too far apart to reach

an accord because Jules can never satisfy her need for adventure.

And so ends my list.

Writing about these films has caused me not only to remember them, but to also

remember the man that made them. Perhaps that’s the true nature of love – the

memory that never dies.

By Ed Garea

This

month, TCM is planning a festival of Francois Truffaut movies. Each Friday

during the month, four or five will be spooled to what I’m sure will be an

eager audience. Many of Truffaut’s films were intensely personal, arising from

incidents or episodes in his life. In the end, though, Truffaut ultimate

scenario was his premature death at age 52 from a brain tumor.

An

avid reader and intense film buff since childhood, Truffaut was a true

autodidact. Beginning his career in films as a critic with Cahiers du

Cinema in the early ‘50s, he made a name for himself with his 1954

essay, “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema,” which called out the old guard of

French directors for their “stodginess,” and stating his preference for

American films, even the low budget B variety. He was also the instigator of

what came to be known as “the auteur theory,” which has since become part and

parcel of our understanding of the intellectual fabric of cinema. For Truffaut,

the creative personality of directors over the body of their work was more

important than individual films themselves. Some of the directors he admired

included Abel Gance, Jacques Becker, Max Ophuls, Roberto Rossellini, Fritz

Lang, Nicholas Ray, and Alfred Hitchcock, a personal idol of Truffaut’s.

But

as a director, while his technical expertise is to be admired, a far more

important factor in evaluating Truffaut is the fact he’s a marvelous

storyteller. All the technical competence in the world is worth nothing if a

director cannot communicate his story to the audience. However, while I’m sure

my colleagues here at The Celluloid Club see him as France’s

greatest director, I see him only as France’s best director since the

establishment of the revolution created by La Novelle vague, taking

a back seat to the body of work of Abel Gance, Jean Renoir, Marcel Carne,

Jean-Pierre Melville, and Jean Vigo.

Be

it as it may, the three of us agreed to present our five favorite Truffaut

films. While it would be easy to plug in what I believe to be his “artistic”

and critical best, I’m taking the other road in that I’m listing what I

consider to be his five most entertaining movies. Put it this way – if I were

listing my five favorite Henry James novels, I would keep in mind that The

Golden Bowl is his best, both critically and artistically, but it is

not my favorite. That would be The Bostonians, which I believe to

have the better story. It’s the same with Truffaut; his most critically

acclaimed may not necessarily be my favorite, and as I lean towards the

psychotronic in a director’s body of work, the reader will notice that this

preference is evident in my choices. So, without further ado, below are my five

favorite Francois Truffaut films.

5. The Bride Wore Black (1968): It’s sort of Truffaut’s homage to

Hitchcock, even down to having Bernard Herrmann write the score. However,

Hitchcock was never this obvious. Jeanne Moreau is

mourning the fact that thugs whacked her fiancée at the church door right after

he and Jeanne tied the knot. She thinks of killing herself, but gets an even

better idea: why not track down the killers and kill them? At any rate, it’s a

lot of fun, as Jeanne dispatches her victims in most interesting ways.

4. Stolen

Kisses (1968): Not only

is this is one of Truffaut’s most beautiful films, but it also shows the growth

and maturity from his Nouvelle Vague days. Continuing the

story of Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), Truffaut’s alter ego from The 400 Blows, we

discover he has been dishonorably discharged from the army for

questionable character. So, he takes on a series of odd jobs while trying to

find his niche in life. At the same time there’s the problematic relationship

with the love of his young life – Christine Darbon (Claude Jade).

Their problem is that they can never find themselves on the same page, which

provides the basis for much of the film’s humor. As I noted before, watch for

the scene where Antoine proposes to Christine. The camerawork is

excellent and the score enhances the action on the screen.

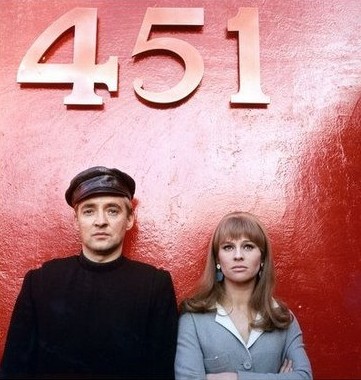

3. Fahrenheit 451 (1966): This Truffaut film will not be

screened during July’s celebration, but it’s a favorite of mine and deserves

inclusion. It’s Truffaut’s first and only film in English; he co-wrote the

screenplay and began shooting before he mastered the English language – and it

shows. He was very disappointed with the awkward and stilted English dialogue,

preferring the French-dubbed version, which he supervised. But no matter, for

it’s still a compelling film based on Ray Bradbury’s book about a future

society where books are burned. Watch for the book burnings: one of the books

being burned is an issue of Cahiers du Cinema, and on its cover is

a still from Breathless, for which Truffaut collaborated on the

screenplay.

2. The 400 Blows (1959): Truffaut’s first and most

autobiographical film, and one I can watch multiple times. It never grows old

for me. While this is not, as many think, Jean-Pierre Leaud’s first film, it is

the film that brought him to the attention of the public and secured a place

for him in cinema history. He went on to play the same character, Antoine

Doinel, for Truffaut four more times. It’s a touching story of a neglected

teenager, brutalized both at home and at school, who responds by acting out:

skipping school, sneaking into the movies, and petty theft. Truffaut’s mise

en scene of a dingy Paris full of arcades, dingy apartments, abandoned

factories, and regular working day avenues helps raise this above other films

of the time. At the end, it presents the question of whether the punishment of

Doinel fitted his crimes.

1. Day For Night (1973): I saw this long, long ago when I

was first married. We went to a theater called The Lost Picture Show, believe

it or not, to see a Truffaut double feature of Day for Night with The

Green Room. Although I enjoyed both, Day for Night especially

moved me. It’s a wonderful film about a director and his problems both on and

off the set, as he has to deal with temperamental actors, an actress

rescheduling because of her pregnancy, problems with the set, and other

emergencies that suddenly crop up, calling for the filmmaker to be a fireman, a

confidant, and a psychiatrist in addition to his directorial duties. It is

extremely entertaining and one of the few Truffaut films I own on DVD.

By David Skolnick

There are only few

directors in the history of cinema who can compare to Truffaut. His films are

incredibly well-made whether it's a comedy or a drama or, as in most cases, a

combination of both. You'd think that because Truffaut made only 21

feature-length films, it wouldn't be that difficult to pick his best five.

After all, I get to select nearly 25 percent of them. But because of the

quality of each movie, the selection process is difficult. It means some of my

favorite films - The Bride Wore Black, Shoot the Piano

Player, Mississippi Mermaid, The Man Who Loved Women and Stolen

Kisses - didn't make this list.

5. Two English Girls (1971): This is a role

reversal of Truffaut's classic Jules and Jim, made in 1962, about

two men in love with the same woman. In Two English Girls, it is

two women in love with the same man, Claude Roc, played by the incomparable

Jean-Pierre Léaud, who stars in more Truffaut's films than any

other actor and is the face of the French New Wave. Two English Girls takes

place around the turn of the 20th century with Claude meeting an English

woman, Muriel Brown (Stacey Tendeter), with the two immediately becoming close

friends. She invites Claude to her family's estate hoping he'll fall in love

with her sister, Ann (Kika Markham). The three are inseparable, but Claude

falls for Muriel, who falls even harder for him. Their families insist they

don't see each other for a year and if they're still in love after that time,

they can be married. Claude spends most of the year having sex with several

women in Paris and with only one month until the year is up, he breaks it off,

devastating Muriel. Ann, who isn't assertive by nature, goes to France to

confront Claude, but instead the two fall in love. While neither relationship works,

the three characters are deeply affected for decades as a result of the

passionate love each sister has for Claude and his love of them. It's a

beautiful yet tragic film that has been wrongfully maligned over the years by

some who can’t appreciate its underlying message of intense love never

fulfilled.

4. The Woman Next Door (1981): Truffaut's

second to last film, released three years before his death, The Woman

Next Door tells the story of Bernard Coudray (Gérard Depardieu), a happily married family man

living in the French countryside who's life gets turned upside down when

Mathilde Bauchard (Fanny Ardant in her greatest role) and her husband move next

door. It turns out Bernard and Mathilde had a passionate love affair years ago.

They try to fight their feelings, but succumb to them. There are a few light-hearted

moments in the film that initially comes off as a romantic comedy. But at its

core, it is deep, dark and tragic with outstanding acting and beautiful

cinematography. And that ending stays with you long after the closing

credits.

3. Day for Night (1973): This film

permanently ended the friendship between Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, probably

the second most important director of the French New Wave movement whose

earlier films were groundbreaking, but made largely inconsistent movies the

rest of his career. Day for Night is a film about making a

film with Truffaut playing Ferrand, a director. Godard sent an angry letter to

Truffaut after seeing the film. He complained that Truffaut’s character and

Jacqueline Bisset, who plays Julie Baker, the lead actress in the fake movie,

called Meet Pamela, don't have a sex scene in Day for Night as

the two were a real-life couple at the time. Godard wrote a letter calling

Truffaut "a liar" and then had the nerve to ask for money for his

next film project. Truffaut's letter in response puts Godard in his place,

calling him "a liar" by posing as a "victim" of the film

industry system despite making whatever movies he desired. As for the film,

it's an excellent portrayal of the difficulties and challenges of making a

movie with the focus not only on the actors of the fictitious film, such as

Bisset and Jean-Pierre Léaud, but also the crew members giving viewers a

complete look at the process. What’s very interesting is the fake film comes

across as trashy, simplistic and dull, sort of the anti-Truffaut movie. The

acting is top-notch with Valentina Cortese stealing many scenes as Severine, a

nearly washed-up alcoholic actress having trouble accepting that her better

days are behind here. Also, kudos to Truffaut, who is great in his portrayal of

the director. It's a beautiful tribute to cinema; a love letter from Truffaut

to film without getting mushy or sentimental.

2. The 400 Blows (1959): This is

Truffaut's debut feature-length film and it's a masterpiece. Before he

made The 400 Blows, Truffaut was a film critic for Cahiers de Cinéma, a French film publication, and made no

secret about what he saw as the shortcomings of the movie industry. Incredibly,

he shows the world how to make a daring, brilliant film and helps create a

movement that changed the face of movies, inspiring numerous directors in the

decades since its release. Rather than stick with the traditional French

formula for making movies, Truffaut championed films with strong, creative

directors who personalize their work. Jean-Pierre Léaud had a small part a year earlier in King

on Horseback, but this is his first leading role – a 14-year-old

playing the 12-year-old Antoine Doinel, strongly based on Truffaut. As

previously mentioned, he'd reprise the character in three other feature-length

films (all are excellent with 1968's Stolen Kisses the best of

the bunch) and a 30-minute short. You can see even at this age why Léaud would become Truffaut's go-to actor in many

films and why at such a young age, he was already a gifted actor. He has a

natural charisma, charm and talent, seemingly so at ease portraying the

mischievous and misunderstood Antoine. Truffaut deserves a lot of credit for

the brilliant filming of this movie, making the gritty, dirty streets of Paris

the young actor's main co-star and helping to highlight the lost, confused

existence of Antoine. Its final scene on the shoreline with a freeze-frame of

Antoine’s face is among the most iconic endings to a film. Many directors,

actors and film fans say this is their favorite movie. It's definitely in my

top 15.

1. Jules and Jim (1962): Just edging

out The 400 Blows as my favorite Truffaut film is this

incredible movie. The plot takes place over a period of about 25 years before,

during and after World War I, depicting the intense friendship between two men –

Jules (Oskar Werner), an Austrian, and Jim (Henri Serre), a Frenchman – that is

stronger than many marriages, and how it evolves because of the presence of

Catherine (Jeanne Moreau, one of cinema's all-time best actresses), an

impulsive, captivating and enchanting woman. Catherine loves both men, marrying

Jules before the war – he and Jim are fighting for opposing countries and

fearful they'll meet in combat. After the war, Jim visits Jules and Catherine,

who have a daughter. But things aren't good between the couple and Catherine,

who's had several affairs, falls for Jim. Jules' love for her is so great that

he agrees to divorce Catherine so she can marry Jim with all three of them, and

the child, living together. But that marriage also has its problems. Jim

leaves, but plans to return when Catherine becomes pregnant with his child.

They don't get back together because of a miscarriage with Jules and Catherine

becoming a couple again. That too is short-lived when the three meet years

later and Catherine wants to get back together with Jim, who loves her but

realizes there's no future for them as a happy couple. The acting is

extraordinary, the voice-over narration by Michel Subor greatly enhances the

storyline – narration can easily kill a movie – and everything works to

perfection from the beautiful cinematography that uses photos, freeze-frame,

archived footage and tracking shots to the storyline adapted from Henri-Pierre

Roché’s book to Georges Delerue’s soundtrack. Passion

and the impact it has on people is something Truffaut focuses on in a number of

films, including The Woman Next Door. While the ending to that 1981

film is outstanding and memorable, the conclusion of Jules and Jim is

even better. This is one of the finest films ever made. It is as much a piece

of art as a master painting, a captivating song or a brilliant poem. It is easily

the best French New Wave movie I've seen, and the greatest French film of

all-time, which is as big a compliment as I can give because no other foreign

country has made more quality movies than France.

No comments:

Post a Comment