A

Guide to the Interesting and Unusual on TCM

The

Last Falcon

By

Ed Garea

When

a major or well-known supporting star passes from the scene we read

about it on the Internet or in major publications, hear it on the

news, and sometimes, TCM will run a little tribute mini-marathon of

their work.

But

when it comes to the lesser-known stars lurking at the bottom of the

bill, unbilled, or even with a hefty resume of “B” credits, we

hear and read little, if anything. Rather than being presented to us,

we actively have to seek it out or risk missing it altogether.

Our

topic today is one of those actors, John Calvert. He came to films

late in life as his primary vocation was that of stage magician, a

vocation at which he excelled for over eight decades, making over

20,000 appearances. He died on September 27, 2013 at the age of 102.

But

even those who knew him as a gifted magician probably didn’t know

he was also in movies. None of the films in which he had a major role

were ever found on the “A” side of the bill, though he did work

as a stunt double or technical adviser on some “A” projects. His,

though, are the sort of stories that make up the crazy quilt called

Hollywood history, filling in the back stories that make such history

so fascinating.

Calvert

did his first magic show at the tender age of eight and began touring

as an 18-year old. At the age of 100, he fulfilled a lifelong dream

by appearing onstage at the London Palladium, and was still

performing only a few weeks before his death, accompanied by his

assistant and wife of over 50 years, Tammy, who survives him.

Calvert

also introduced many stage tricks during his long career, including

firing a woman from a cannon into a box suspended overhead on the

stage. He had his wife play an organ as they floated above the stage

and over the heads of the audience. And it was he who originated the

trick of sawing off the head of a spectator using a giant buzz saw.

When

he performed the trick onstage during World War II during bond

drives, Hollywood stars would often come forth to assist in the act.

It wouldn’t be unusual to see Gary Cooper, Cary Grant, or Marlene

Dietrich being sawed in half onstage or made to disappear in a box.

“One night,” he said in a 1998 interview, “Danny Kaye came out

impersonating Hitler. The Marines grabbed him and put him in the buzz

saw and he’d cut his head off. Then we put his head in a meat

grinder and out came German sausages!”

Besides

the stage, Calvert also broke into films as a hand double in

MGM’s Honky Tonk (1941). He earned $600 a day

doubling for Gable, who played a gambler. It was Calvert’s hands we

saw in those intricate scenes maneuvering cards; tricks only a

seasoned magician or gambler could pull off.

Having

gotten the acting bug, Calvert appeared in his first role in RKO’s

1943 war drama, Bombardier, in an unbilled role playing –

what else? – Calvert the Magician. His first credited role was in

William High’s 1944 JD melodrama for Monogram, Are These

Our Parents? where, again to no one’s surprise, he played

a magician. In 1945, he managed 4th billing in The

Return of the Durango Kid, for Columbia, as one of a gang of

bad guys that run afoul of Our Hero, The Durango Kid. His last film

was an adventure film title, Dark Venture, which he

produced, wrote, directed, and starred in for a little company called

First National Film Distributing in 1956.

Although

Calvert was never able to rise higher in motion picture features than

the “B” level, he did achieve some lasting fame as the last man

in the movies to play Michael Arlen’s suave detective, The Falcon.

It's

commonly assumed that The Falcon was invented by RKO in order to have

a detective series for George Sanders once the deal allowing them to

bring Leslie Charteris’ suave detective, The Saint, to the silver

screen expired. This story, as with many Hollywood stories, is only

half-true. RKO did require a new detective to replace The Saint. They

had already made five films in The Saint series. The original starred

Louis Hayward as Simon “The Saint” Templar, but the last four

switched the starring role to RKO contractee Sanders.

Charteris

not only didn’t like the film adaptations for his character, but he

also strongly disliked Sanders as Templar. In this, he was not unlike

other authors who sold their work to the studios only to see their

literary efforts returned into cheap programmers. However, while

other writers kept their mouths shut and counted the money, Charteris

would complain long and loud to whomever lent an ear. After a couple

of years of listening to him complain, RKO was as sick of him as he

was of them, and began lining up a replacement. After all – a

detective series is a detective series. Just switch the plot a little

and no one will care about the difference.

A

reader at the studio came across a short story titled Gay

Falcon by Michael Arlen in a 1940 edition of Town &

Country magazine. The story made its way to the RKO ladder

and it was decided that this was RKO’s escape hatch. They quickly

bought the rights and set about – as studios inevitably do –

changing the characters.

In

the Arlen story. the character’s name was Gay Stanhope Falcon. As

conceived by Arlen he freelanced as an adventurer and troubleshooter;

a man with a talent for engaging in dangerous enterprises and keeping

his mouth shut. RKO, looking for a Saint tie-in, changed Arlen’s

adventurer into an English gentleman detective with a weakness for

gorgeous women. They also re-christened him “Gay Stanhope

Laurence,” and like Simon Templar, he has an alias, “The Falcon,”

though for what reason he’s called this is never explained. As with

Templar, Sanders would play Laurence.

The first film in the

series, The Gay Falcon, if fact, was so close to the

preceding Saint series that the film was given the

working title of Meet the Viking in order to keep

Charteris from finding out. But, alas, Charteris found out anyway,

and – predictably – was furious, calling the film “so

shamelessly liable as to allow many dull-witted audiences to think

they were still getting The Saint.” It was a dead-on assessment. He

then filed suit against RKO for unfair competition, which was later

settled out of court. Charteris later got a revenge of sorts in his

1943 novel, The Saint Steps In, when a character refers

to The Falcon as “a bargain-basement imitation” of The Saint.

Charteris,

however, was not the only one dismayed by RKO’s new twist on

matters. Star Sanders also had little use for the new series. Sanders

had been featured as of late in some very popular “A” productions

such as Rebecca, Foreign Correspondent, Rage

in Heaven, and Fritz Lang’s Man Hunt. Having tasted

the Good Life he believed himself too important an actor for this

sort of nonsense and demanded his release. RKO was only too happy to

oblige him – it was a good cost-cutting move – and came up with

the idea of having Laurence’s character killed off, only to be

replaced by his brother. To play the brother, named Tom Laurence, RKO

cast Sanders’s real life brother, Tom Conway, who made his debut in

RKO’s 1942 film, The Falcon’s Brother.

Conway

proved such a hit that he went on to play The Falcon nine more times

before RKO finally pulled the plug in 1946 after The Falcon’s

Adventure. The series had pretty much burned itself out and RKO

figured enough was enough. But The Falcon was not yet done. A

production company named, appropriately enough, Falcon Pictures

Corporation, revived the detective for three low-budget films

– Devil’s Cargo (1948), Appointment With

Murder (1948) and Search for Danger (1949)

– all distributed by Film Classics. All three movies starred John

Calvert as The Falcon – now named Michael Watling. The Falcon was

now a working private eye that also employed tricks of magic to

flummox his foes. The films earned back enough to cover their cost,

but were not big hits. The budgets were such that they made the RKO

Falcon series seem lavish by comparison. The character later moved to

radio and later to television in a short-lived syndicated series in

1954-55. Michael Watling, a now played by veteran actor Charles

McGraw, was now an American espionage agent.

For

those who collect movies, both Devil’s

Cargo and Appointment With Murder are

available on DVD at Amazon.

As

long as I’m on an RKO “kick,” having covered The

Falcon series, now is a good time to plug my TCM movie recommendation

of the week: also from RKO, and also starring Tom Conway.

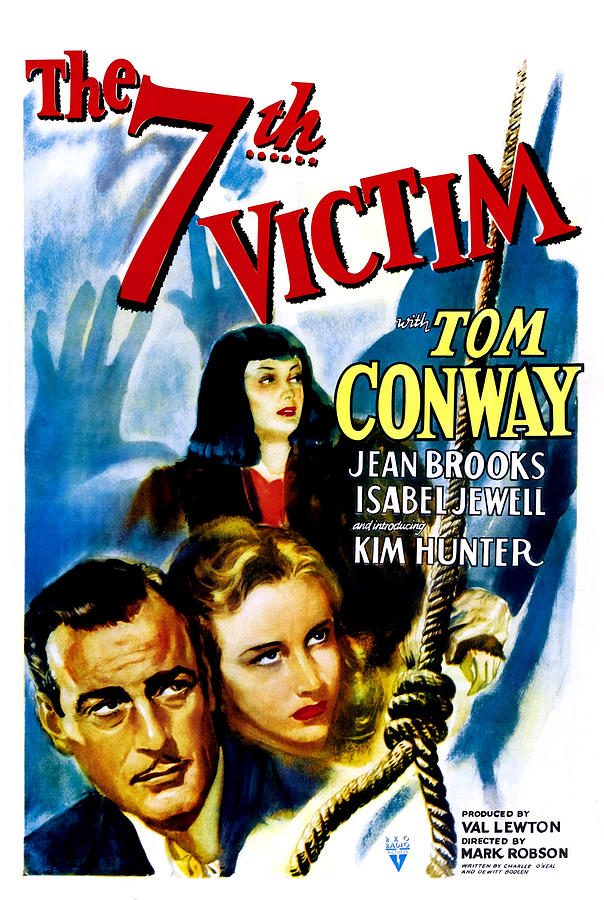

October

18, 11:15 pm – The

Seventh Victim (RKO, 1943) – Director: Mark

Robson. Writers: Charles O’Neal & DeWitt

Bodeen. Cast: Tom Conway, Kim Hunter, Jean Brooks, Isabel

Jewell, & Hugh Beaumont. B&W, 71 minutes.

Long

before Ira Levin scared the pants off ‘60s audiences with his novel

about devil worshippers in Greenwich Village, Rosemary’s

Baby (which Roman Polanski turned into a classic horror

film), Val Lewton was doing the exact same thing for ‘40s audiences

with this finely crafted horror film.

The

main difference between them was that Levin knew he had hot stuff, as

did Polanski when bringing Levin’s bestseller to the screen.

Lewton, by contrast, was simply looking for a story to fill a

pre-chosen title by his bosses at RKO.

Though

Lewton was a producer at RKO, he was on one of the bottom rungs of

the production ladder, being assigned to the B-Unit, where his job

was to make cheap programmers to fill out the typical package RKO ran

in its theaters. He’s been termed by some critics as “The Prince

of Poverty Row,” which is ironic when we consider that his salary

as a producer at RKO was a princely $250 a week. He also had three

inviolable rules when making a film: (1) Each film was to cost no

more than $150,000; (2) Each film was to run 75 minutes at the most;

(3) The story would conform to a title of the studio’s choosing. A

job to die for; in fact, the pressures from the job eventually

brought on the heart attacks that ended his life at the early age of

46.

The

Seventh Victim conforms perfectly to this design. Here we

have the pre-approved title, such like The Cat People or I

Walked With A Zombie, for which Lewton has to find a story. There

was good news and bad news for Lewton on this project. The good news

was that, thanks to the grosses for Cat People and The

Leopard Man, studio interference – and limiting the film to 75

minutes – would not be in place for this feature. The bad news was

the Jacques Tourner had done such a wonderful job in directing the

two films that he was promoted to the A-Unit, leaving Lewton without

a director.

But

for Lewton, it was first things first. He needed a story. When he had

that, then he would get a director. The original story for the film,

by Bodeen (who previously wrote Cat People and would

later write Curse of the Cat People) was about an

orphaned girl caught in a web of murder set against the background of

the Signal Hills (California) oil wells. If she didn’t discover who

the killer was, she would become his seventh victim. Lewton didn’t

like the idea. He had an idea of his own that he thought might fit

the bill and brought in writer Charles O’Neal. Perhaps between the

three of them they could flesh it out, which they did in a burst of

time-pressure inspiration. Lewton then solved his director problem by

promoting film editor Robson to the position. Robson edited I

Walked With A Zombie and The Leopard Man for

Lewton, and Lewton thought highly of him.

Now

let it be said here and now that The Seventh Victim is

not the perfect horror film. In fact there are several holes in the

plot so large one could drive a truck through them. There are good

reasons for these, as we shall see later, but first, a brief synopsis

for those who haven’t yet caught the film.

Mary

Gibson (Kim Bunter in her first role, so we know she came cheap) is a

student at a private school somewhere in upstate New York. One day

she’s called into the office of the Headmistress, where it is

explained to her that her sister (and only living relative)

Jacqueline, has unexpectedly cut off her tuition with not even so

much as a “howdy-do.” Mary’s reaction is one big “Huh?” She

leaves school to come down to the city, looking for Jacqueline. She

discovers that Big Sis sold her cosmetics firm and has disappeared.

This leads Mary on to a dark world of Satanism in the picture

postcard world of Greenwich Village and the Big Sister who is

desperately trying to escape. The art directors at RKO, Albert S.

D’Agostino and Walter E. Keller, did a marvelous job creating the

mise en scene of Greenwich Village from the existing set on RKO’s

back lot. Several posters on IMDb commented that the set looks

uncannily like an Edward Hopper painting “translated to film.”

It’s a perfect description that matches my reaction when I first

saw the film.

Now

– as to those plot holes. Let’s just say that seeing isn’t

necessarily believing. Yes, those plot holes are there,

I can’t deny that. But also take into consideration that this is

Lewton we’re dealing with here; a man who doesn’t make a habit of

plot holes, especially of the size we find in the movie. There is no

movie ever made that was separate from its history. In other words, a

movie doesn’t spring out of the head of a producer or director (for

you auteurists out there) full-grown as Athena did

from Zeus’s head. All movies have what can be called backstories,

events that shape the final version of the film we see and which

result from a collaborative effort in shaping the final version, or

some backstage political shenanigans from forces outside the producer

or director’s control, usually having to do with money.

In

the case of Lewton, I refer to two authoritative books in my library

about this multi-faceted man: Val Lewton: The Reality of

Terror by Joel E. Siegel (Viking, 1973), and Fearing

the Dark: The Val Lewton Career by Edmund G. Bansak and

Robert Wise (McFarland, 2003). According to both accounts, The

Seventh Victim was originally slated by RKO as an A-feature,

a reward for Lewton’s high grosses. RKO always was in search of

someone who could bring in big box office. They failed with Orson

Welles, could they strike gold with Val Lewton?

They

might well have with this film. It has the requisite atmospheric

terror, and, like all good horror films, leaves the horror deeply in

the mind of the viewer. But RKO execs over the years have never been

happy unless they can screw something up completely; to snatch defeat

from the certain jaws of victory.

So

the question now becomes, “How did they do it this time?” Easy.

They waited until the final draft of the script was complete, then

asked Lewton who he going to assign to direct. When Lewton answered

“Robson,” the execs went loco. “But he’s never directed!”

they said. Lewton answered that Robson had already directed much of

the film, which only stiffened their opposition. They handed Lewton

an ultimatum: Either Robson goes, or you must trim the film to 75

minutes or less. Lewton stood by his employee. Bye-bye 90-minutes;

Hello 71-minutes. As the scenes were already filmed and RKO cut the

budget for reshoots, Lewton had to cut the best he could. The result

is what we now see of the film. As it stands, The Seventh

Victim is a wonderful film. Just think of much more

wonderful it would have been had those cuts not been forced upon

Lewton.

OTHER

FILMS OF DESERVING INTEREST

October

19, 12:00 am – Miracles For

Sale (MGM, 1939): Tod Browning’s last

directorial effort for MGM stars Robert Young as a magician who owns

a magic shop. He likes to expose phony spiritualists that like to

prey on the vulnerable. During one such séance, Young meets Florence

Rice, who wants him to help her find a killer before she becomes the

next victim. As Leonard Maltin notes, the film “is a slick whodunit

that cheats its audience a bit too often." It also presents us

with the most obvious red herring in the history of film mysteries.

However, it is Browning’s last film. It failed at the box office

and he was fired as a result. Whatever magic he possessed in the

silent days was long gone, and his last sound films seem like he’s

learning as he goes. By the way, also watch this for its superb

supporting cast, including Henry Hull, Astrid Allwyn, William

Demarest, and two of my favorites, Gloria Holden and Frederic

Worlock.

October

21, 10:00 pm – Knife

in the Water (Kanawha

Films, 1962): Roman Polanski’s feature film directorial debut is a

film one would never expect to see in Communist Poland. It’s a

finely nuanced character study of a bored, materialist couple who

pick up a hitchhiker and take him to their boat. The hitchhiker’s

presence unhinges the fragile bond of their marriage and trouble

ensues. When the ruling Brahmans of Poland got a peek at this, they

reacted like one would think they’d react: they banned it. His

career over, Polanski left Poland and wound up a starving artist in

Paris. It wasn’t until a print escaped a couple of years later that

the resulting cheers assured Polanski of a future as a director. He

then headed to England, where his next film was Repulsion.

TCM dropped the ball with one, though. It should be shown back to

back with Ashes

and Diamonds,

which plays on October 22 at the ungodly hour of 6:15 am.

No comments:

Post a Comment