By Ed Garea

May 9

9:00 am Purple Noon (Times Film, 1961) Director: Rene Clement. Cast:

Alain Delon, Marie Lafortet, Maurice Ronet, Elvire Popesco, & Erno Crisa. Color,

115 minutes.

Tom

(Delon) is the poor friend of rich Philippe (Ronet). The two are vacationing in

Italy and Philippe shows no signs of wanting to cut the trip short. Philippe’s

father has promised Tom $5,000 if he can persuade his friend to pack up and

return to America. However, Tom comes to the realization that he will never

collect because Philippe shows no inclination whatsoever to return home.

Philippe has the life that Tom wants: a nice big boat, loads of cash, and a hot

girlfriend in Marge (Lafortet). So why not kill Philippe and take his place?

That is exactly what Tom does. If you haven’t yet figured out why this all

sounds so familiar, then let me inform you that Tom’s last name is “Ripley,”

and this is the first cinematic version of her novel The Talented Mr.

Ripley. Both versions have their strong points. Purple Noon is

well photographed and acted, though the ending differs from both the book and

the later version. If you’ve seen the Matt Damon version, see this one as well.

It’s worth it.

1:30 am A Hatful of Rain (20th Century Fox, 1957) Director: Fred Zinnemann.

Cast: Eva Marie Saint, Don Murray, Anthony Franciosca, Lloyd Nolan, & Henry

Silva. Color, 109 minutes.

There

were two currents that came together in the ‘50s to give dramas more of a sharp

edge. One was the slow lessening of the censorship stranglehold that had been

in effect since the mid-30s. The second was more of a tragedy: the scourge of

addiction that spread across the country since the end of World War II. The

first film to really shine the light on this was Otto Preminger’s The

Man With the Golden Arm in 1955. Once the studios saw the box office

receipts, the rush was on to find similar projects for the screen.

One

such project came to 20th Century Fox in the form of a drama by

playwright/actor Michael V. Gazzo (many will remember him for his Oscar

nomination for his role as Frankie Pentangeli in The Godfather, Part II)

entitled A Hatful of Rain. A hit on the Broadway stage, it had been

lauded as one of the finest examinations of the subject of drug abuse.

The

film takes place in an apartment shared by Korean War vet Johnny Pope (Murray),

his pregnant wife Celia (Saint) and his younger brother Polo (Franciosca). They

are anxiously awaiting the visit of overbearing family patriarch John Sr.

(Nolan). Senior is hypercritical of everything his sons do and is especially

ticked off that he can’t secure a small loan from his younger son. What he is

not privy to is the fact that Polo’s savings have long since disappeared into the

vein of his older brother, who has become a heroin addict. Even Celia is

unaware of what her husband’s been up to and the rest of the film explores the

relationship between the three main characters.

One

thing we can see right away from this synopsis is that what makes for a fine

drama on Broadway does not necessarily translate into a movie. Add that to the

fact that the studio insisted that the film be shot in Cinemascope, and all

hope for an engrossing drama as lost. A Hatful of Rain is

dependent on the illusion of intimacy and Cinemascope totally destroys that

illusion, burying it in a format expressly made for epic films. Director

Zinnemann’s opinion of Cinemascope was no less withering, calling it

“a ridiculous format, shaped like an elongated Band-Aid.”

It tended to defeat the director in his choice

of the precise point he wanted the audience to look at; instead, the viewers'

eyes went roaming over those acres of screen...I remember spending much time

inventing large foreground pieces to hide at least one-third of the screen.

Zinnemann

tried his best within the confines he was given. Carl Foreman handled the

adaptation – uncredited, as he was still suffering from the infamous Blacklist

– and Zinnemann secured the cooperation of the NYPD Narcotics Squad, even

gaining entry into the hospital ward at Rikers Island, where many of the

hardest cases were treated. The result of all this effort was a fine picture,

marked by several excellent performances, but a pronounced failure at the

all-important box office.

May 11

6:00 am The Indestructible Man (Allied Artists, 1956) Director: Jack Pollexfen.

Cast: Lon Chaney, Jr., Casey Adams, Mirian Carr, Ross Elliott, Stuart Randall,

Robert Shayne, & Joe Flynn. B&W, 70 minutes.

By

the time he starred in this low-rent effort, Lon Chaney, Jr.’s film career was

definitely on the skids. Alcoholism had reduced him to character roles and

infrequent ones at that. But his name still had cache, especially in the horror

genre, and in this enjoyable outing he is condemned criminal Charles “The

Butcher” Benton, sentenced to the chair on the testimony of his former

partners, who turned State’s evidence. After he’s juiced, his body is diverted

to the laboratory of a Dr. Frankenstein wannabe, Professor Bradshaw (Shayne) and

his assistant (an uncredited Joe Flynn, better known for his turn as Captain

Binghamton in McHale’s Navy), who are working on a cure for cancer.

Towards this end, the good Doctor in reanimating Chaney’s body with massive

jolts of electricity. (Wait! Wasn’t Chaney killed this way?)

The doc discovers that all this electricity has made Chaney’s body impervious

to penetration. In the opening scene, we see the doc trying to inject Chaney

with a hypodermic only to have the needle bend – in fact, the scene is so good,

the director shows it twice. Coming back to life, Chaney shows his gratitude

toward the doctors by killing them.

Chaney

is after two things: the $600,000 armored car payroll he hid, and revenge on

his double-crossers. Eventually the body count causes even the police to notice

and they begin looking for him. They track him through the testimony of his

lawyer, Paul Lowe (Elliott), who confesses to hiring the gang to rob the

armored car and also reveals that Chaney has been using the sewer system to hide

from the police. Eventually the cops catch up with Chaney and dispatch him for

good in a most redundant way.

The Indestructible Man has been featured on Mystery Science Theater 3000, and is best described by film critic

Michael Weldon in his Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film: “Lon

Chaney, Jr. made a lot of bad junky movies, but this one is great junk.”

Trivia: Chaney doesn’t utter a

single word throughout the movie, with the reason given as the massive jolts of

electricity burned out hid vocal cords. But in reality, his alcoholism has so

affected his mind that he was unable to remember many of his lines.

2:15 am The Twonky (UA, 1953) Director: Arch Oboler. Cast: Hans

Conried, Billy Lynn, Gloria Blondell, Ed Max, & Janet Warren. B&W, 72

minutes.

When

television bloomed on the American cultural landscape in the late ‘40s, the

oft-repeated tag line was that “this is what will kill of movies.” The studios

certainly saw the little box as a threat – many innovations made during the

‘50s, such as Cinemascope and its related ilk were direct answers to that

threat. Science-fiction writer Oboler saw in this a great idea for a movie. The

only problem would be one of plot, how to realize the idea. And the one word

that came to me when the movie ended was “misfire.” Oboler had taken a great

idea for what could have been brilliant satire and fumbled it.

Conried

is philosophy professor Kerry West. His wife, Carolyn (Warren), is going to

visit her sister. To keep him company while she’s away, she purchases a television

set. West soon discovers the set has a mind of its own. It lights his

cigarettes, washed his dishes, opens bottles of Coke for him, and even ties his

tie. But it also makes arbitrary decisions for him as well. For instance, it

won’t allow him a second cup of coffee, and when he tries to play a classical

symphony on the phonograph, it destroys the record and replaces it with a

march. It even scares off a female bill collector (Blondell) who has come to

repossess it. The question for Professor West is now one of how he can rid

himself of this menace before it drives him mad.

Because

of its subject matter and the fact this film is so rarely shown (before

watching it last year, I hadn’t seen it on television for over 30 years), the

curiosity factor alone makes it a “must see.”

Trivia: Following

production, the film sat on the shelf awaiting a distributor while Oboler

produced the first major 3-D film of the Fifties, Bwana Devil,

which was also a disappointment.

May 12

2:30 am Early Summer (Shochiku Eiga, 1951) Director: Yazujiro Ozu.

Cast: Setsuko Hara, Chishu Ryu, Chikage Awashima, Kuniko Miyake, Ichiro

Sugai. B&W, 124 minutes.

This

is Ozu’s follow-up to Late Spring, and the family is scrambling to

find 28-year old Noriko (Hara). She works and her brother sees her independence

as impudence. When her boss suggests a 40-year old bachelor as a marriage

partner, her family urges her to accept, but her course of action startles

everyone involved. This is the second of an Ozu’s trilogy, culminating with the

brilliant Tokyo Story (1953).

May 13

2:15 pm Washington Merry-Go-Round (Columbia, 1932) Director: James Cruze. Cast:

Lee Tracy, Constance Cummings, Walter Connolly, Alan Dinehart, & Arthur

Vinton. B&W, 78 minutes.

In

what almost seems like an early version of Frank Capra’s later Mr.

Smith Goes to Washington, Tracy is Button Gwinnett Brown, an idealistic

young man elected to Congress and determined to rid Capitol Hill of corruption.

What he finds is a place dependent on the sort of corruption he’s trying to

root out and his efforts spur his detractors to trump up a recount and strip

him of his seat. The similarities between this and the later Mr. Smith are

interesting – both leading men visit the Lincoln Memorial for inspiration and

to combat feelings of despair. Even the characters played by the female leads (Cummings

and Jean Arthur) are similar. However, there isn’t any evidence to the extent

that the later film was spawned from the earlier one. In the writing credits to

Mr. Smith there is no mention of Washington Merry-Go-Round, or of

Maxwell Anderson, who wrote the story from which Jo Swerling completed the

film’s screenplay.

2:45 am The 400 Blows (Janus Films, 1959) Director: Francois Truffaut.

Cast: Jean-Pierre Leaud, Guy Decomble, Claire Maurier, Albert Remy, &

Patrick Auffay. B&W, 99 minutes.

Question:

Is that any serious film buff out there who has not yet seen this movie?

Renowned as the first great film to come from the French “New Wave” movement of

the late ‘50s, it tells the story of young Antoine Doinel, who remains

resilient despite a pair of uncaring parents and blockheaded schoolmasters.

Truffaut based the screenplay on his own adolescence – the French title of The 400 Blows comes from the idiom faire

les quatre cents coups. It means, "to raise hell." But the irony

is that Doinel isn’t really raising hell, he’s just trying to survive his

adolescence.

Trivia: The 400 Blows was

shot in less than two months on actual locations, at a loss of approximately

$50,000. Look for cameos by Jeanne Moreau and Jacques Demy. Also look for the

director himself riding next to Antoine in the centrifuge ride at the fair.

4:30 am Masculin-Feminin (Royal Films, 1966) Director: Jean-Luc Godard.

Cast: Jean-Pierre Leaud, Chantal Goya, Marlene Jobert, Michel Debord, &

Catherine Duport. B&W, 103 minutes.

This

is essential viewing for the serious film buff as one of the points where

director Godard turns from mere observations of life to politicized

observations about that same life as the influence of Marxism is making itself

felt in his films.

Following

his discharge from the army, a young French Marxist named Paul (Leaud) takes a

job as an interrogator for a public opinion poll concerned with the opinions

and attitudes of French youth. After watching a woman murder her husband on a

Paris street, Paul strikes up an acquaintance with Madeline (Goya), a young

singer who openly admits to using sex to further her career. He moves in with

Madeline and her roommates, Catherine (Duport) and Elisabeth (Jobert),

involving himself intimately in their relationship, joining in on their

get-togethers in cafes, discotheques, coffee shops and the cinema, where they

engage in conversations on birth control, civil and military authority, East

versus West, and even James Bond.

Paul

is still undecided about his future when his mother passes away, leaving him a

good-sized inheritance that he uses to buy a small, unfinished building. One

day while inspecting it, he falls – or jumps – to his death, leaving behind a

pregnant Madeline.

Trivia: The film was shot

in Sweden. Ingmar Bergman, no fan of Godard, found out and went to see it. His

comment? “A classic case of Godard – mind-numbingly boring.”

May 14

10:00 pm Where the Sidewalk Ends (20th Century Fox, 1950) Director:

Otto Preminger. Cast: Dana Andrews, Gene Tierney, Gary Merrill, Bert Freed, Tom

Tully, Ruth Donnelly, & Karl Malden. B&W, 95 minutes.

When

asked about this film, Preminger answered that he knew nothing about it. When

we dig a little deeper into Otto’s amnesia we discover what may be its cause: Where the Sidewalk Ends was a miserable

failure at the box office – the lowest grossing film that Fox released that

year. Filmed at a cost of $1.475 million, it made back only $1 million.

But

as serious film buffs have discovered time and time again, never judge a film

by its box-office receipts. Preminger, who first cut his teeth in film noir in

his rightly praised 1944 classic Laura provides another great

character study of a violent cop whose inability to curb his violence

ultimately becomes his undoing. He’s had more complaints filed against him than

any other officer in his precinct, but as he’s roughing up social misfits, the

complaints are ignored as the ravings of the guilty. But when he goes too far and

kills a suspect, his world begins to crumble. Preminger captures it

magnificently, aided by screenwriter Ben Hecht and fine performances by star Andrews,

supported by Tierney, Merrill, and Tully. This film is a definite must for

every film noir fan.

Trivia: This film was

originally dramatized under the title “Night Cry” for the radio series

“Suspense” in January 1949. It starred Ray Milland in the Andrews role.

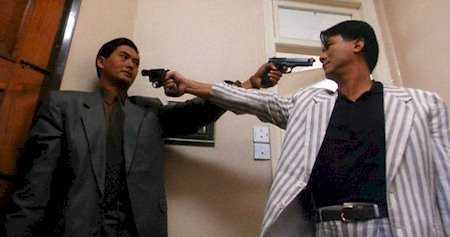

1:30 am The Killer (Golden Princess, 1989) Director: John Woo.

Cast: Chow Yun-Fat, Sally Yeh, Kenneth Tsang, Chu Kong, Lam Chung, & Shing

Fui-On. Color, 111 minutes.

Woo

is to action films what John Ford is to Westerns or James Whale to horror

films. Woo first hit his stride as a director with A Better Tomorrow in

1986, establishing his reputation as mater in ultra-violent action gangster

films and thrillers. He has been cited as a major influence on directors such

as Sam Raimi and Quentin Tarantino (a lot of the style of Tarantino’s Reservoir

Dogs – the suits, the Mexican stand-offs, and the double guns – is

attributable to The Killer). Woo, in turn, admits to being heavily

influenced by French director Jean-Pierre Melville.

The

plot of The Killer is Woo at his best: Assassin Ah Jong (Chow)

accepts one last hit in hopes of using his earnings to restore the vision of

his girlfriend Jenny (Yeh), a singer he accidentally blinded during an earlier

hit (though she doesn’t know it was he that blinded her). When his boss

double-crosses him he reluctantly joins up with Inspector Li (Lee), the cop who

is pursuing him. Together they go to confront the gangsters out to kill them –

and do so in pure Woo style.

Trivia: The Killer was

filmed in 92 days at a cost of $2 million. It might never have been made at all

except for the insistence of the film’s star, Chow Yun-Fat, who was also the

studio’s biggest star . . . At the end of the film, the body count stood at

120.

5:00 am The Secret Six (MGM, 1931) Director: George Hill. Cast: Wallace

Beery, Lewis Stone, Johnny Mack Brown, Jean Harlow, Marjorie Rambeau, John

Miljan, Clark Gable, Paul Hurst, & Ralph Bellamy. B&W, 83 minutes.

The Secret Six marks

the first foray of MGM into what can only be described as Warner Brothers’

territory, and it is a most successful and interesting foray at that. A bootlegging

operation, run by Scorpio (Beery) has set its sights on City Hall. Rival

reporters Hank (Brown) and Carl (Gable) are investigating, all the while being

entertained by Anne (Harlow) a gang moll assigned by Scorpio to keep the

reporters distracted. In response to the arrival of Scorpio’s gang on the

scene, a special police force is created. Calling itself “The Secret Six,” it

is comprised of six asked men representing the “greatest force of law and order

in the U.S.” They use Carl and Hank to gather evidence on Scorpio’s operation,

and when the gang later kills Hank aboard a subway car, Scorpio is arrested and

brought to trial.

Trivia: This was the first

pairing of Gable and Harlow, who went on to make such films as Red Dust (1932), Hold

Your Man (1933), China Seas (1935), Wife Vs.

Secretary (1936), and Saratoga (1937), the last film

Harlow made before her untimely death. The two were such close friends that it

was assumed they were also lovers, but that was not the case. On the other

hand, Harlow and co-star Beery completely loathed each other, and couldn’t

stand being in the same room when not filming.

No comments:

Post a Comment