Why

We Love Being Scared and the Movies Based on That Love

By

Steve Herte

My

teenage obsession with the cosmic horror tale imagined by Howard

Phillips Lovecraft stems from when I found The

Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe in

our basement and read it from cover to cover. Poe fascinated me and

still does; and I believe he must have been a major influence on

Howard Phillips Lovecraft. Poe was long gone when Lovecraft was born,

but if you read “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket”

(1838) and then pick up “At the Mountains of Madness” (1931) by

Lovecraft you will find that they link together nicely. Both tales

take place in Antarctica and both involve a hidden malevolent

creature identifiable only by the chilling sound it makes, which both

authors quote verbatim.

I

don’t remember who among my high school friends recommended

Lovecraft to me, but I recall becoming hooked on “The Colour from

Out of Space” and went on to collect every book and collection of

his wonderfully creepy stories. I learned later on that my current

favorite author, Stephen King, is quoted as calling Lovecraft “the

twentieth century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror

tale” and that he was responsible for King’s own bent toward the

macabre, as he made clear in his semi-autobiographical Danse

Macabre.

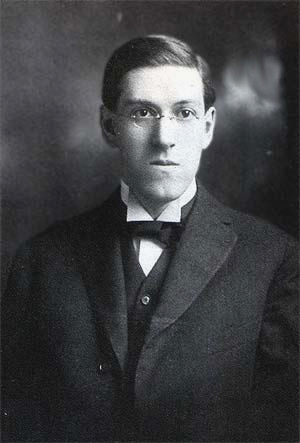

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, on August 20, 1890, to Winfield Scott

Lovecraft, a travelling salesman, and Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft

of Massachusetts Bay Colony descent, Howard lost his father quite

early. Winfield was hospitalized with psychosis in 1893 and died of a

paralysis brought on by syphilis (they called “nervous exhaustion”

back then).

Raised

by his mother, two aunts, and a maternal grandfather who introduced

him to Gothic Horror, Howard was encouraged to read and read

voraciously, especially during his frequent periods of illness,

becoming interested in chemistry and astronomy. His sleep was

disturbed by night terrors, which would eventually inspire him to

write the poem “Night Gaunts.”

With

the trauma of his grandfather’s death in 1904 and the resulting

impoverishment due to mismanagement of the estate, the family was

forced to move to smaller living quarters. The higher mathematics he

needed to become a professional astronomer eluded him and caused a

“nervous breakdown” that would ultimately cost him his high

school diploma. Living a reclusive life with his mother, he wrote

mainly poetry until 1913. Then a letter of complaint he wrote to a

pulp magazine, “The Argosy,” got the notice of editor Edward F.

Daas, who invited him to join the United Amateur Press Association.

Thus, in 1917, Howard was writing fiction stories including “The

Tomb” and “Dagon” (his first published work).

In

his own words:

“In

1914, when the kindly hand of amateurdom was first extended to me, I

was as close to the state of vegetation as any animal well can be...

With the advent of the United I obtained a renewal to live; a renewed

sense of existence as other than a superfluous weight; and found a

sphere in which I could feel that my efforts were not wholly futile.

For the first time I could imagine that my clumsy gropings after art

were a little more than faint cries lost in the unlistening world.”

His

frequent letters drew a coterie of correspondents that included

Robert Bloch (who wrote “Psycho”), Clark Ashton Smith, and Robert

E. Howard (responsible for “Conan the Barbarian”). Things were

looking up until 1919, when Howard’s mother, after bouts of

hysteria and depression, was committed to the same hospital where his

father died. She succumbed of complications from gall bladder surgery

in 1921.

A

few weeks later, Lovecraft met Sonia Greene at a convention in Boston

and though he was seven years her junior, they married in 1924 and

moved into her Brooklyn, New York, apartment. Howard’s initial

delight in New York turned into intense dislike when Sonia’s poor

health, her stay in a New Jersey sanitarium, and financial hardship

(she lost her hat shop) forced her to move to Cleveland for

employment, leaving him alone in then-seedy Red Hook. This, coupled

with his inability to find work, spawned the short stories, “The

Horror at Red Hook” and “The Shunned House.” Also during this

period he wrote “Cool Air,” “Herbert West – Re-Animator,”

“The Unnamable,” “The Lurking Fear,” “The Outsider,” and

“The Hound.” He returned to Providence in 1927 and the two agreed

to divorce. The best part of Howard’s New York experience was his

association with a group of men dubbed the Kalem Club, which included

his protégé Frank Belknap Long and several friends who encouraged

him to publish in “Weird Tales,” another celebrated pulp

magazine.

The

last 10 years of Lovecraft’s life were the “big bang” of his

writing career and included such stories as “The Dunwich Horror,”

“The Colour Out of Space,” “The Call of Cthulhu,” and the

novellas The Shadow Over Innsmouth, The Shadow Out of Time,

and At the Mountains of Madness. Also during this period he

ghosted “The Mound,” “Winged Death,” “The Diary of Alonzo

Typer,” and “Under the Pyramids” (written for Harry Houdini),

and his only novel The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. His

travels to Quebec, Charleston, St. Augustine and venerable sites in

New England provided enhanced settings for his tales. Again,

financial hardships forced him to downsize living arrangements with

his surviving aunt. If this weren’t enough, he learned of the

suicide of Robert E. Howard. Cancer of the small intestine and its

resulting malnutrition caused Lovecraft constant pain until his death

on March 15, 1937.

I

can’t help but wonder if Lovecraft noticed the parallels to Poe’s

life in his own: the loss of his father, being raised mainly by

women, financial difficulties, and frequent moving. But as they say

about blues musicians, “You have to pay your dues to sing the

blues.” Howard experienced horror in his own life, which gave him a

deep well from which to draw his terrifying stories such as “The

Beast in the Cave” (1905) and “The Alchemist” (1908). His

imagination was limitless. In his early years he created the ultimate

evil book The Necronomicon, first mentioned in the short story

“The Hound” (1924), supposedly written by the mad Arab Alhazred

(actually a pseudonym for himself at the age of five) and

incorporated so thoroughly into his stories that one would believe

that such a book actually existed (I actually thought I found it in

the Boston Main Library). Robert Bloch created the mythical book and

equally loathsome tome De Vermis Mysteriis in his “The

Shambler from the Stars” (1935) and Lovecraft adopted it into his

mythos of Cthulhu, an ancient horror and extra-dimensional Elder God.

Lovecraft’s

nurturing of Robert Bloch, August Derleth, Fritz Leiber and Donald

Wandrei not only caused their careers to blossom but thanks to them,

the “Cthulhu Mythos” was continued and spread as each author

incorporated part of Lovecraft’s pantheon of elder gods and

unnamable horrors. It was through them that Arkham House Publishing

Company was formed (Arkham is Lovecraft’s renaming of Salem) and

Lovecraft’s stories were finally put into book format, albeit

post-mortem, in “The Outsider and Others” (1939). His novella,

The Shadow over Innsmouth (1936), was the closest he came to

publishing a book during his lifetime.

Other

authors who were touched by and whose writings were affected by (and

whose names were changed and incorporated into his stories) included

Arthur Machen and Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett (known as Lord

Dunsany). Even after the last of these men, Bloch, died in 1994, the

Cthulhu Mythos continued on and the “Great Old One”

appeared in the South Park episode “Mysterion Rises”

(November 3, 2010), the second part of a three-part arc beginning

with “The Coon” and followed by “Coon 2: Hindsight.” An

oil-drilling company that caused a major spill in the Gulf of Mexico

releases him when they mistakenly think that drilling on the Moon

will fix their former error.

Thus

did Poe lead me to Lovecraft and thence to Bloch, who I understand

completed Poe’s unfinished final tale “The Lighthouse” in 1977

under the title “The Horror in the Lighthouse.” I’m currently

in the process of obtaining that story.

Movies:

Though

there have been many adaptations of Lovecraft’s work, as seen

below, practically none are of first-rate quality, excepting the

first listed, The Haunted Palace. The rest have simply served

as excuses for gross-out horror. None have done well at the

box-office, while several went straight to video. The only adaptation

that has any sort of reputation among film fans and especially those

of horror, is The Re-Animator, which has gained a cult

following over the years.

The

Haunted Palace (AIP, 1963): Although writer Charles Beaumont

took a few lines from Poe’s 1839 mood poem and had Vincent Price

recite them near the end, the film is actually based on Lovecraft’s

story “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward.” Directed by Roger

Corman.

Die,

Monster, Die, aka Monster of

Terror (AIP, 1965): A very loose adaptation of “The

Colour Out of Space.”

The

Dunwich Horror (AIP, 1970) Well, it’s based on “The

Dunwich Horror.” IMDB provides the perfect synopsis: H.P.

Lovecraft meets Hollywood: Wilbur Whateley wants to help the Old Ones

break through by consulting the Necronomicon, and Dr. Armitage must

stop him. Attractive females are added to fill out the plot.

Island

of the Fishmen, aka Screamers, from

the Italian L’isola degli uomini pesce (Dania

Film,1979): A mish-mosh of Lovecraft’s “The Shadow over

Innsmouth” and The Island of Doctor Moreau by H.

G. Wells.

Re-Animator (Empire

Pictures, 1985): Based on “Herbert West – Re-Animator.”

From

Beyond (Empire Picture, 1986): Based on “From Beyond.”

Curse (TWE,

1987): Loosely based on “The Colour Out of Space.”

The

Unnamable (Image Entertainment, 1988): Based on “The

Unnamable.”

Pulse

Pounders (Empire Pictures, 1988): Based on “The Evil

Clergyman.”

Bride

of Re-Animator (Artisan, 1989): Sequel to Re-Animator.

The characters are from Lovecraft, but the story is original.

Dark

Heritage (Sterling Pictures, 1989): Based on “The

Lurking Fear.”

Shatterbrain aka The

Resurrected ( Lions Gate, 1991): Based on “The Case of

Charles Dexter Ward.”

The

Unnamable II: The Statement of Randolph Carter (Lions

Gate,1993): Again, a sequel with only Lovecraftian characters, not

the story.

Necronomicon:

Book of the Dead (August Entertainment, 1993): An

original story based on the concept.

Lurking

Fear (Full Moon Entertainment, 1994): Based on “The

Lurking Fear.”

Castle

Freak (Full Moon Entertainment, 1995): Based only

slightly on “The Outsider.”

Bleeders aka Hemoglobin (A-Pix

Entertainment, 1997): Based on “The Lurking Fear.”

Cool

Air (Lurker Films, 1999): Based on “Cool Air”

(1926) and written during his unhappy stay in New York.

Rough

Majik aka Dreams of Cthulhu Volume 2 (Lurker

Films, 2000): A TV short based on the works of Lovecraft and the Cult

of Cthulhu, but no particular story.

Dagon (Lions

Gate, 2001): Based on “Dagon” and “The Shadow over Innsmouth.”

Beyond

Re-Animator (Lions Gate, 2003): Another sequel with only

characters by Lovecraft.

The

Call of Cthulhu (MicroCinema, 2005): Based on “The

Call of Cthulhu.”

Masters

of Horror, Episode 2 (IDT Entertainment, 2005): A TV

series. The second episode is based on “Dreams in the Witch House.”

Beyond

the Wall of Sleep (Lions Gate, 2006): Based on “Beyond

the Wall of Sleep.”

Cthulhu (Regent

Releasing, 2007): Based loosely (very loosely) on “The Shadow over

Innsmouth.”

Chill (Rojak

Films, 2007): Another adaptation of “Cool Air. ”

Colour

from the Dark (Vanguard Cinema, 2008): Italian version

of “The Colour Out of Space.”

Beyond

the Dunwich Horror (Scorpio Film Releasing, 2008): A

better adaptation than the first The Dunwich Horror.

The

Dunwich Horror (Active Entertainment, 2009): A TV movie

based on “The Dunwich Horror.”

The

Color Out of Space (Brinkvision, 2010): German

version of “The Colour Out of Space.”

The

Whisperer in Darkness (MicroCinema, 2011): Based on “The

Whisperer in Darkness.”

13:

de mars, 1941 (Big Belly Film, 2004): A Swedish film

“inspired” by the works of Lovecraft.

Kammaren (Big

Belly Film, 2007): Another Swedish film only “inspired” by the

works of Lovecraft.

Fyren (Big

Belly Film, 2010): Yet another Swedish film “inspired” by

Lovecraft with overtones of Edgar Allen Poe’s last tale “The

Lighthouse.”

In

addition, Rod Serling’s excellent series, Night Gallery,

featured two faithful adaptation of Lovecraft:

“Pickman’s

Model” (Season 2, Episode 11): Lovelorn Mavis Goldsmith

ignores her reclusive art teacher Pickman's warning not to follow him

home.

“Cool

Air” (Season 2, Episode 12): A Gothic love story about a woman and

a man who lives in a refrigerated apartment.

Does anyone know exactly how many gold snake belts that were made for Sandra Dee in the 1970's movie the Dunwich Horror??

ReplyDeleteAlso does anyone know how to identify which belts and robes were actually used in this movie??